The Glamour of Doctoral Research

19/10/2020 - 3.48

Dr Benjamin Halligan, Director of the Doctoral College

This sounds like an odd title, or argument, for a blog post! But the more I talk to doctoral researchers, the more I discover that things that may seem, objectively, marginal are actually often central to the lived experiences of being a researcher.

Doctoral research can suggest long and unsociable hours in libraries or studios or archives or laboratories, maybe holding down a number of jobs, and something of a modest lifestyle for the duration of the research too. And to engage in doctoral research can be to experience a bit of envy for the lifestyle of others – seeing one’s friends getting on in the world while you continue to work, and often live, within a university environment and culture: still writing, still learning, still hitting those deadlines, while they pull in salaries and enter professional life.

But in my experience this feeling of being temporarily “left behind” can be countered by a consideration of the perspectives of just those getting on in the world, as they themselves look at friends engaging in doctoral research. That seemingly enviable “getting on”, especially in the early years beyond graduation, can be to begin at the bottom. It may mean that they’re never more than a few steps away from the office photocopier and coffee-maker, or stuck in the corner of a room with the same few people year in and year out, or considering themselves in a temporary holding job until a career proper begins (… something which can, of course, take some time). And, jarringly, entering this professional world can suddenly wrench one out of a research culture, and so end the opportunities to discuss and explore interests and passions with likeminded others. Those looking back at their friend who remains within the university and its vibrant culture, gaining higher (indeed, the highest) qualification, moving forward to master absolute specialisms, might also feel a twinge of envy. Indeed, the doctoral researcher, particularly once a couple of years into their research, often seems to be in the process of becoming a “somebody”, and leaving the others behind.

That is, the doctoral researcher is establishing themselves as an expert – and becoming a voice in their field. And this establishment can happen in a multiplicity of exciting ways: developing an online presence for yourself and your work, beginning to speak at conferences (and with the travel and encounters that can go with that), becoming a go-to person in terms of talking about your discipline and what your research has revealed, delivering university-level teaching, joining various scholarly and academic organisations and receiving invites and opportunities accordingly. Your circle of research contacts and friends is rapidly internationalised, and you begin to engage not only with your university, but with various other institutions (academic and non-academic) too. And all this is in addition to actually engaging in the generation of new knowledge – which can then mean being the first person to begin to delve into certain archives, or excavate sites, or run a series of experiments on specialist equipment, or begin to recover cultural artefacts long since forgotten, or push forward research designed to make improvements to people’s lives. And that new knowledge is something which you become the owner of, and speaker-about. In that respect you can become a wanted person: someone that more established academics want to pull into their orbits, get into their journals, speak (or chair panels) at their conferences and symposia. This is the trajectory of becoming the “go-to” person – an additional benefit to developing a skillset of the highest order, and undertaking research of international importance. You emerge as the expert: the person others look for. And you’ll be introduced as much too: “this is…”, “doing a PhD in Cyber Security…”, “looking at news ways to…”, “just back from field research in…”, “working with the institution of…”, “who spoke at…”, “just published in…”

As someone who has co-edited a number of books, what excites me more than working with established “names” in various disciplinary fields is being the first to publish early career researchers, or even pre-early career researchers (that is: those engaged in doctoral research). This is helping to bring new ideas and new perspectives, and a new energy, to the discipline. Without this, and drawing on the same old tried and trusted paradigms and ideas (and authors), the evolution of the discipline will slow – and I won’t find my own preconceived ideas challenged and refreshed. And I encounter these early career researchers on the doctoral research circuits: via conferences (even looking at programmes of those you’re not attending yourself), via social media, via the recommendations of others, via new publications and, of course, from those I supervise or examine. And, indeed, a further encounter can be just via people getting in touch with me: “Sorry for the email out of the blue, but I thought you might be interested in my new article / blog post / online presentation on…”. But it isn’t just me looking to work with new researchers: expert analysis and opinion, and expert voice and presence, is needed now more than ever – from consultancy to activism to expert witness, from working with NGOs and charities to working at the cutting edge of research projects with substantial, and sometimes urgently needed, societal benefits. As universities orientate their research cultures to strategies of impact in the wider world, the person conducting doctoral research can readily find themselves at the forefront of taking research and ground-breaking ideas to new audiences.

My final consideration here is that often your time then becomes your own. You’re not locked into a 9-5 routine at the behest of others. And you’re not typically located in one fixed position, but are mobile – across campuses, and beyond, even across different countries. Adaptability occurs, along with evolving abilities to work in different, and often colourful, environments. (Surely doctoral research selfies are some of the best selfies out there?) Every good doctoral researcher needs to be a citizen of the world, and that comes with the international perspective and connections that you gain. Getting to grips with organising your time effectively, to keep the variety of activities ticking over, is also an essential skill. And, crucially, this needs to include a bit of glamour: meeting new people, holding the floor at conferences, making people think differently, travel, launches and events, getting your name out there via publications, talking to others as an expert in your field. Difficult to think of a term other than “glamorous” for all this!

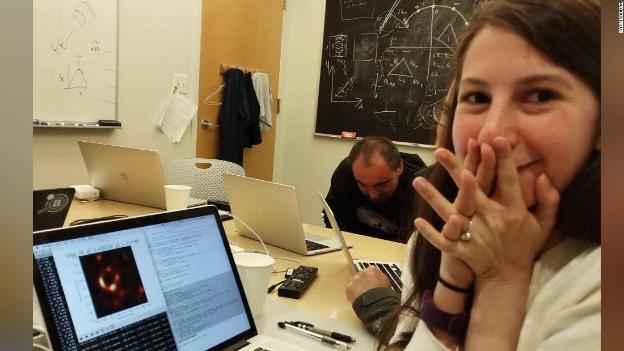

Katie Bouman was a PhD researcher in Computer Science and AI at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she led on the development of an algorithm to visualise a supermassive black hole at the heart of the Messier 87 galaxy, 55m light years from Earth. This photo, seen around the world, is the moment of the first generation of that image.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)