Footballers in the 24th (2nd Sportsmen’s) Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers in the Great War. Part Two – Private Charles Reuben Clements

21/06/2022 - 1.55

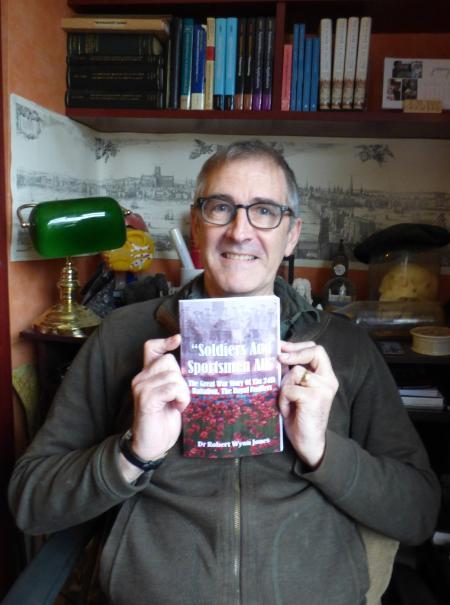

Bob Jones

Adapted from my book Soldiers And Sportsmen All – The Great War Story Of The 24th Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers

Introduction

One of the men who served in the Battalion in the Great War was Private Charles Reuben – “Charlie” – Clements, a former shop assistant – and my maternal grandfather.

Charlie was born at home in Hammersmith on January 12th, 1896, the son of Charles Ernest Clements, a carman and contractor, and his wife Jessie, nee Percy, a part-time music teacher. Home was 109 Yeldham Road, a small end-of-terrace Victorian house at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac off Fulham Palace Road. Charlie received his education at Latymer School in Hammersmith. However, he was forced to leave school early, aged seventeen, in 1913, after his father died suddenly, in order to enter the workplace – as an assistant in a gentlemen’s outfitter’s shop – to help provide an income for his family.

Charlie was evidently a conscientious man, with a strong work-ethic. He never gambled, although he did “do the Pools”, which he considered to be a game of skill rather than chance. And, after an unfortunate early experience at a friend’s coming-of-age party, he never drank. He had a dry sense of humour. When my mother wrote to inform him of my – premature – birth in 1958, he wrote back that he was “delighted of course to hear that Robert Wynn is progressing so well” and “flattered at first to hear he resembled myself but on reading ... that he was short of ... hair and putting on weight am rather in doubt”. In his free time, he enjoyed a range of sporting pursuits.

Soldier

Charlie voluntarily enlisted in the 24th (2nd Sportsmen’s) Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers on May 30th, 1915, and was given the regimental number 3526. It is evident from his surviving “Medical History” (Army Form B178), dated June 4th, 1915, that he lied about his age when he volunteered, claiming to be twenty-two when he was actually only nineteen - possibly because he looked about sixteen. Also, that he stood only 5’6” tall, and weighed only 9st4lbs.

Private Charles Reuben “Charlie” Clements, in army uniform at the beginning of his service. Source: Author’s Collection.

After enlistment, Charlie was sent to Hare Hall Camp in Romford, where the 24th Battalion had just set up its base, for training. He emerged from training as a Private soldier and 1st Class Signaller. As a Signaller, one of his responsibilities on the battle-front would be to relay communications. In the Great War, this was generally done by using field telephone networks, rather than by the hitherto conventional means of signalling with flags (using Semaphore), or with lamps or mirrors, or with a Heliograph (using Morse Code). It would involve the laying and constant repairing of miles of telephone cable in and around front-line trenches, often under fire. And it would be dangerous work. In April, 1917, the then Signals Officer for the 24th Battalion, Second Lieutenant Cyril Francis Stafford, would suffer a mortal wound while supervising the laying of telephone cables near Vimy Ridge.

Charlie went on to serve with the 24th Battalion on the Western Front for three years, fighting in the Battles of the Somme in 1916; in the Battles of Arras and Cambrai in 1917; and in the First and Battles of the Somme, and the Battle of Havrincourt, the first of the Battles of the Hindenburg Line, in 1918.

Private Charles Reuben “Charlie” Clements in army uniform toward the end of his service. This photograph was taken on August 17th, 1918, while the 24th Battalion was stationed near Bapaume (around a month before CRC was wounded). Note the three “Overseas Service Chevrons” on his lower right sleeve, one for each year of service overseas; and the “Good Conduct Chevron” on his lower left sleeve. Note also the customary cigarette. Source: Author’s Collection.

Charlie was reported in the Battalion War Diary as having been killed on September 10th, 1918. In fact, according to his “Casualty Record – Active Service” (Army Form B103), he had been seriously wounded by shrapnel – or possibly shell fragments – in the left arm (elbow) and leg (thigh, knee and ankle) on 12th, almost certainly in an operation in the Battle of Havrincourt, which took place on that date. He was carried from the field to the 5th Field Ambulance, and from there he was taken – either by an actual ambulance or a horse-drawn cart - to No. 46 Casualty Clearing Station at Bac du Sud, just south-west of Arras. From there, he was transferred to No. 12 General Hospital in Rouen on September 13th. And from there he was repatriated to the U.K., on board His Majesty’s Hospital Ship “Formosa”, on 15th. He spent the remaining two months of the war receiving treatment in hospitals in Keighley and Shoreham, and some time after the war convalescing in the Star and Garter Home in Richmond in Surrey. He had “copped a Blighty one”. His only visible scar was the size and shape of a teardrop, under his eye.

Private Charles Reuben “Charlie” Clements in army uniform after the Great War (note the medal ribbons). Charlie’s left eye appears to be injured; his expression, haunted – or is that my imagination? Source: Author’s Collection.

Sportsman

After the war, in 1919, Charlie returned to work, in Harrods, a luxury department store in Knightsbridge in the fashionable West End of London, which at the time provided employment for large numbers of ex-Servicemen. In 1921, he came to own and manage his own gentlemen’s outfitter’s shop at 180 South Ealing Road in Ealing in Middlesex, and to live in the modest rooms above.

Charlie also returned to his sporting pursuits. He played football for the amateur side Ealing Wednesday, so-called because most of the players were independent shopkeepers, and they preferred to play on early closing day, which was Wednesday, rather than on Saturday, so as not to lose their best trading day’s takings.

Ealing Wednesday Football Club. The occasion is clearly that of a cup final. It is not known for certain which, although the cup in the centre appears to be the same as that displayed on the right of Image (below,) which is either the Ealing Hospital Cup or the Roose Francis Cup. The location is also unknown, but could be Wimbledon’s old ground at Plough Lane, featuring the south stand acquired from Clapton Orient in 1923. Charlie is seated in the front row, fifth from the left. Source: Author’s Collection.

The team had a particularly successful season in 1923-24, ending up as winners of the Ealing Hospital Cup, the Harrow Charity Shield, the Kingston and District Wednesday League, the Philanthropic Cup, and the Roose Francis Cup, and as runners-up in the Hounslow League and the Middlesex Mid-Week Cup. They also won the London Mid-Week Cup in 1930-31.

Ealing Wednesday Football Club. Taken at the end of the 1923-24 season. Based on the legible parts of the inscriptions, the trophy on the left is the Kingston and District Wednesday League Cup; and the one second from the left, the Philanthropic Cup. By a process of elimination, the two on the right must be the Ealing Hospital Cup and the Roose Francis Cup, but it is not known which is which. Charlie is seated in the front row, second from the right. Source Author’s Collection.

Charlie reportedly also played on a “boot money” basis for the professional side Fulham, who were in the Second Division of the English League, in the early 1920s. However, he always supported, and would have liked to play for, his local team, Brentford. Incidentally, he also represented the Thames Valley Harriers at long-distance running, and Middlesex at bowls, both, again, on an amateur basis. He also played tennis to a high standard, including at the prestigious Queen’s Club in West Kensington in London, which, incidentally, his father had helped to build in 1886. Here, he played with Fred Perry, who went on to win three Wimbledon Men’s Singles titles, in 1934, 1935 and 1936.

Home Guard

On October 21st, 1921, Charlie married Gladys Mabel Millard, familiarly known to him as “Mabs”. And in 1934, “Mabs” had a baby daughter, Peggy Anne, my mother. The family would come to enjoy taking in not only sporting events but also sundry other entertainments such as comedy shows or musicals at the Chiswick Empire or the “Q” Theatre (in Kew), or, on special occasions, in the West End. During the Second World War of 1939-45, Charlie joined the Middlesex Home Guard (of “Dad’s Army” fame), one of whose duties was to help to man a heavy anti-aircraft gun battery in Gunnersbury Park. According to one family story, which may or may not be entirely true, at the beginning of the Vergeltungswaffen or Vengeance-Weapon campaign directed against London, in June, 1944, he and his comrades, while attempting to shoot down a low-flying V-1 flying bomb or “Doodlebug”, instead inadvertently shot up part of a nearby building!

Later Life

Charlie remained close throughout his later life to a number of his comrades from the Great War, especially to William - “Billy” - Bentley, who he regarded as once having saved his life, and who was his best friend; and to Archibald - “Archie” - Bannister, who was his best man. The old soldiers would all meet up in London every November, on the Friday closest to Remembrance Sunday, and would then all go together to the Cenotaph in Whitehall to attend the National Service of Remembrance. Like so many of his generation, Charlie scarcely ever spoke, at least outside this closed circle, of his wartime experiences. However, he did once allude to the suffering of the horses on the Western Front (he had grown up around horses). He never committed to paper any of the thoughts or feelings he might have had about the war. These he took with him to his grave.

Charlie died, after a sudden unexplained illness, on April 27th, 1958, aged sixty-two, and was cremated in Mortlake Cemetery on May 2nd. I was only three months old when he died, and, sadly, have nothing to remember him by bar these bare facts about his life, some faded photographs, and replacements for his lost 1914-15 Star, British War and Victory medals (“Pip, Squeak and Wilfred”). I am strangely comforted, though, by the knowledge that he would have had memories of me. My mother told me that she took me with her to see him when he was in what turned out to be his final days, and that he regained consciousness long enough to recognise me, and to lay his hand on my head, before drifting away again, for the final time.

Biography

Dr Robert Wynn – Bob - Jones is a retired professional geologist and palaeontologist, an interested amateur archaeologist and historian, and an occasional walking tour guide. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books, including “Soldiers And Sportsmen All – The Great War Story Of The 24th Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers”. He is a member of the Western Front Association and the Royal Fusiliers Historical Society. And he is proud to have been a contributor – albeit a minor one – to the Thiepval Database Project, the essential aim of which is to put faces to the names of the “missing” of the Somme. He lives in London.

Bob Jones can be contacted via e-mail at: lostcityoflondon@sky.com

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)