Football in World War One

08/11/2022 - 3.40

Richard Marks

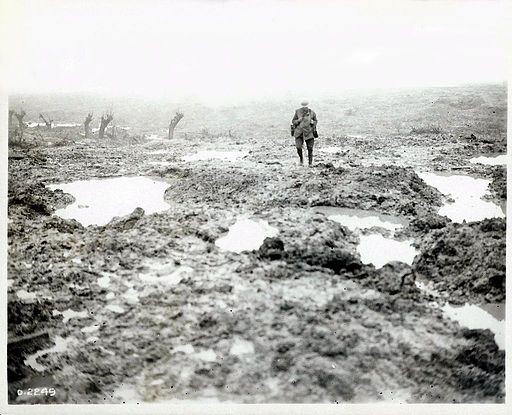

Mud! The common perception of the First World War is of mud, foetid shell holes, broken remains of trees and villages, soldiers wading up to their knees in water in trenches, or climbing out to go ‘over the top’ and walk into hails of machine gun fire. If this was true, how did ‘Tommy’ get time to play football?

The war reached a stalemate in northern Europe, after the British Army stopped the German advance at the Battle of Mons in August 1914, and the French Army met and stopped the German Army at the First Battle of Marne in September. The massed machine guns and artillery deployed by both sides forced the troops to dig in for protection and trench warfare began.

The Battlefield of Passchendaele in 1917. Source: William Rider-Rider, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The First World War was just that, a world war, and whilst the ‘Western Front’ in France and Belgium was a key theatre of operations, the British Army was active in many other theatres away from the ‘mud of France’. Britain’s soldiers could be found on the plains of the middle-east where the war did not experience the stalemate and trench warfare seen in France, in Greece and other islands of the Mediterranean as well as supporting Italy, another member of the alliance against the Central Powers of Germany; the Austro-Hungarian Empire; the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. In all of these theatres, a war of movement, manoeuvre and counter manoeuvre was the normal. In Italy, even with Italian entrenchments in the mountainous areas constant thrust and counter thrust could be seen in the river valleys below.

British Recruitment Poster (1915). Source: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

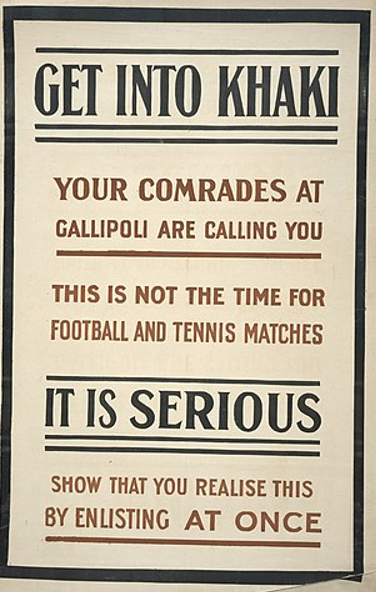

Britain’s Army in France, The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was exhausted by the beginning of 1915 and a campaign of enlistment was undertaken to convince young men to ‘join up’. Recruitment posters linking the team work of football to the army and carrying suggestions that the time for games was past and the time to enlist to defend the country had come could be seen across the country.

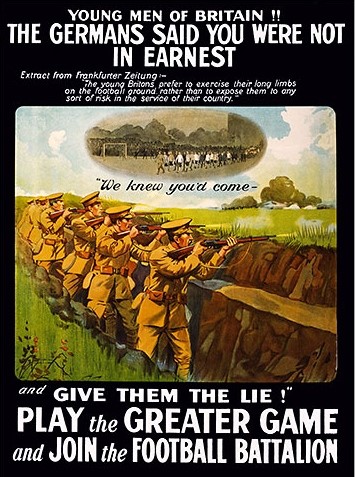

The Army created the ‘Pals’ battalions during this time, to encourage men who worked together, or had a common trade to enlist together. One of these was the ‘Footballers’ Battalion’ of the Middlesex Regiment (17th Battalion), the core of which consisted of a group of professional footballers who had joined up together to serve. Part of the motivation experienced by the footballers was of course a sense of duty, but also a response to the words used in German newspapers, such as the Frankfurter Zeitung, accusing the British of ‘cowardice’.

British Recruitment Poster (1915). Source: Unknown, under Crown Copyright, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The footballers went to France alongside many other young men and women who went to serve, and for many looking back at the war from today, their fate was to spend their time in rat infested and partly flooded trenches, returning home, if they were lucky, in 1918 after the armistice.

A damaged British trench during a period of rain. Source: National Library of Scotland, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

British Communication Trench, 1916. Source: Ernest Brooks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The image of roughly made, waterlogged trenches was the exception, the armies on the Western Front mainly keeping their trenches immaculately repaired and maintained. Whilst not comfortable they were serviceable and often dry and safe from sniper and machine gun fire. The infantryman spent most of his time bored, repairing the trenches, or other tasks, only leaving the trench for occasional raids across ‘No Man’s Land’ between the trenches to capture German soldiers for interrogation by Intelligence officers or to repair the barbed wire, usually at night.

The question of how ‘Tommy’ could play football still remains. If the British infantryman spent all his time in the trenches, a game of football was clearly not possible, so how could they arrange a game?

British and German Lines near Loos-en-Gohelle, July 1917 (British Lines on the left). Source: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The British soldier (and his allies in the French, Belgian, Portuguese, Indian, Australian and New Zealand armies among many others) did not spend all their time in the trenches. In the British Army, unless an Allied or German offensive was in progress, the men only spent five days in the front-line trenches before being relieved by another unit, at which point they spent a further five days in reserve before being relieved and spending time away from the lines in the rear areas. The soldier’s rest away from the lines was when there was time for football.

There were other units in the British Army who were not sent down into the trenches and who may have had the opportunity to organise a football game. The artillery was stationed behind the front lines but within range to support the troops in the trenches when required. The standard British artillery piece of the war was the 18 Pounder Field Gun with a range of up to five miles.

Australian Battery, Ypres, 1917. Source: Unknown Photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The First World War was a war of new technologies and two new military inventions became important parts of the British Army, neither of which were located in the trenches. In 1916, a new unit was created to take advantage of one of these new technologies. The Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps took its new machines to war for the first time at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. This unit later became more famous as the Royal Tank Corps and was responsible for operating the world’s first tanks. These machines were kept in Tank Parks well away from the front where they received the great amount of maintenance that these new vehicles needed, until they were needed for an offensive.

Volunteer Chinese labourers cleaning a British tank in 1917. Source: Chatham House, London, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The war saw the second new invention used by every nation involved in the war and with it the creation of a new sphere of warfare, as for the first time the sky became a battle-ground. The British Army, after initial scepticism, adopted the aeroplane and by 1916, it had become an important part of the war. The Royal Flying Corps’ aerodromes were located well away from the front lines where flat grass fields could accommodate their fragile machines but still within range to patrol the air above the battlefields.

The Royal Army Medical Corps was an important part of the care provided for wounded or ill soldiers, and whilst a small number of their personnel were located close to the lines in casualty clearing stations, the majority were a long way from the battle fields where the field hospitals could be safely placed away from the dangers of the war. Also located mainly in the rear areas (although they also ran narrow-gauge light railway trains up to the front) could be found the men of the Railway Operating Division (ROD) who kept the railways in France running to supply the troops with ammunition, food and medical supplies as well as providing trains to take wounded soldiers or those on leave back to the coast and on home to Britain.

ROD men repairing a damaged railway, 1918. Source: National Library of Scotland, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

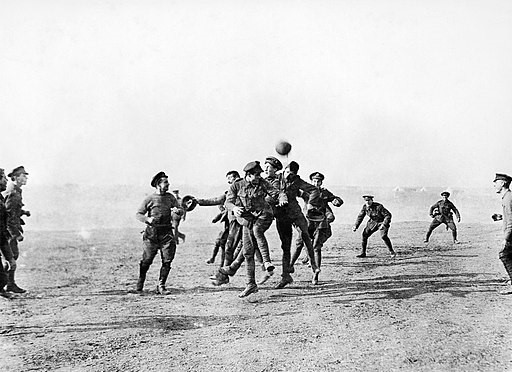

The units stationed away from the frontlines and those rotated out to rest areas had time to play football. The sport was a popular form of exercise within the British Army as a means to both keep the troops healthy and build a sense of team work and increase moral and loyalty to a soldier’s brother’s in arms their ‘esprit de corps’. As many working-class men played the game in some form it was an easy way for the army to build fitness and team work in its troops.

British Troops playing football, Salonika, Greece, Christmas Day, 1915. Source: Varges Ariel, Ministry of Information, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In France it was a simple game to organise, the materials to make a pair of goals could be as simple as four poles and a rope. From these basic items, a pitch could be created anywhere at a moment’s notice. It was important for the Army in France, not only as a means to keep the men fit but also, through organised competitions or challenge matches between battalions, regiments or even between the army and the navy, as a way to keep the men occupied and away from the cafés and other places of entertainment. When a competition was organised most of the men would attend to watch and support their comrades.

Indian Cavalry taking part in a Football Match, Estrée, France, 1915. Source: The British Library, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Some units had time to form a permanent football team to represent the unit in competition against other elements of the army. The Royal Flying Corps squadrons aircrews often had time on their hands when not flying, and the ground staff had spare time when their colleagues were in the air. These kinds units were able to form teams, often with their own football strips in unit colours which were frequently photographed by unit photographers.

Number 54 Squadron Royal Flying Corps, 1918. Source: David McLellan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One curiosity of football during the war were scenes, caught on camera, where troops were seen playing or lining up in gas hoods and respirators. Sometimes these photographs were arranged specifically for the photographer but on many occasions the men played in protective equipment to accustom them to wearing this early chemical warfare protection and also to learn to become able to run short distances in them.

Army Football Team wearing PH Helmet Gas Hoods, 1916. Source: Agence Rol, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This leaves the historical onlooker with one question…when a foul was committed how did the officer refereeing the match know who to book?

Foul! Source: Agence Rol, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Biography

Richard Marks is a published freelance historian based in Berkshire. His main areas of research are industrial and railway history, military history (focusing mainly on the first and second world wars) and also the history of science. Richard's current areas of research are the Royal Flying Corps during world war one, the development of space exploration and the history of British Rail. He is also a Lead Tutor with the WEA, teaching courses related to his areas of research as well as general Victorian history.

Richard had previously spent a long career working in technology as a system engineer working with British manufacturing companies across a broad range of sectors, giving him an in-depth knowledge of industry and business, which has proved valuable in interpreting economic history.

Richard is currently finalising a PhD in economic history which examines the impact of railways on industrial development in rural counties during the nineteenth century, and is also writing a new book on British Rail Engineering Limited (BREL) which is due for publication in 2023, followed by a new book examining the Wantage Tramway Company. Richard's first book, a technical history of the Avro Lancaster was published by Osprey Publishing, but he is now a contracted author with Pen and Sword books.". Richard’s twitter handle is @industrypast

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)