The Life and Times of a Team Player

25/11/2021 - 4.43

Carole Wright

“War Hero” and “Football Star” was the title of an article about my father in a recent edition of The Bolton News. I’m not sure he ever thought of himself in that way. He spoke rarely of his war service or of his footballing years when I was a child. It was only in later life that a few details emerged, usually in conversations with his grandchildren. So why the article in the local paper?

It was prompted by the receipt of a message on my Ancestry.com account. This came from Andrew Rowley who explained that he and a group of supporters of Chelsea Football Club were researching and recording the final resting places of ex- Chelsea players. They have a presence on Facebook called Chelsea Graves Society and information on ex-players can also be found on the Chelsea website. They had found a John Lewis Sherborne playing for Chelsea 1938-9. Andrew had messaged a distant relative who had the same John Sherborne in his tree and it was he who then passed on my tree details to Andrew to allow him to make this initial contact. Could I provide him with any more details about my father which, with my permission, he would forward to the local paper?

Time to unearth the old scrapbook compiled by my mother, the photograph album assembled by the family for my father’s 90th birthday and my father’s Soldier’s Service Book (SSB). Some of this would give Andrew a little more pre-1945 information which he had acknowledged to be fairly sparse.

My father John Lewis Sherborne (known as Jack) was born 1st May 1916, to John William and Sophia Sherborne nee Howcroft, the youngest in a family with five surviving children. Four babies were already deceased and his eldest brother was to lose his life the following year, a soldier in the World War One conflict in Iraq. They enjoyed outdoor activities and were a sports-loving family. His father and brothers played various sports locally both competitively and successfully.

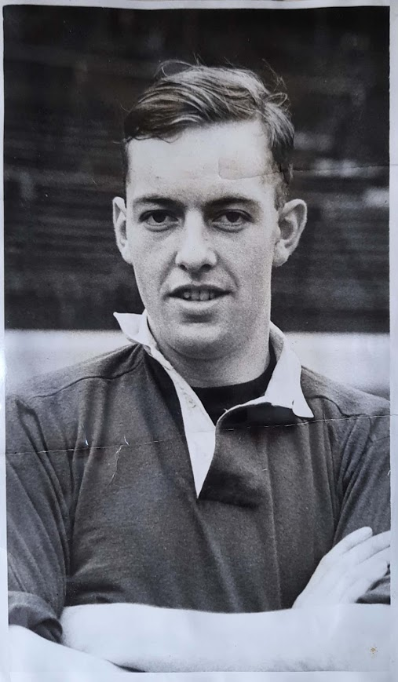

John Lewis Sherbourne. Source: Author's Collection

Football was my father’s sport of choice winning a Bolton Boys Federation medal for the season 1933/4 and making a name for himself in the local Bolton League playing for Hunger Hill Temperance Club. Soon he was moving up the ranks to join Chorley Football Club champions of the Lancashire Combination. Here according to a newspaper cutting dated 29th Feb 1936 he “…has done so well in Combination football that he was being ‘watched’ by several League clubs and has now signed for Chelsea F.C. aged 19.”

He began his Chelsea career playing for the reserve team in the London Combination. Very successfully it seems as in the Chelsea F. C. Chronicle (the official programme of the football club) dated 27th April 1938, he is credited with 14 goals and is joint top scorer in his first full season. However, his first taste of League football as centre forward against Wolverhampton Wanderers in December 1937, was not the most auspicious of starts. According to the Chelsea programme dated Sat 25th December 1937, comments on the game. He “…was the third centre forward to be called upon to lead the front line in three weeks” due to first team injuries. It goes on to say “It would not be fair to judge John Sherborne too critically on his emergency appearance on such treacherous foothold; opposed too by England’s almost impassable pivot.” His League debut came a couple of months later in March 1938, as outside left against Brentford, where according to a newspaper cutting entitled “Sherborne Makes Good”, he scored a goal and was credited with an assist.

Chelsea players watching a demonstration by their trainer. Source: Author's Collection

1938 was a good year for my father. He was becoming a rising star at Chelsea playing more League games and on 22nd June 1938, back in Bolton he married Edith Hulme. They had met on a blind date which had been set up by a friend of my fathers from his days as a bell ringer at Deane Church Bolton. They seem to have spent their honeymoon on the Isle of Man sometime during that summer. My mother spoke of them being there with a group of Chelsea footballers and their wives and girlfriends living the “high life” as she put it. I’m not sure if they were there for a football tournament or just a break but my mother was impressed that they stayed in a hotel and drank champagne at one shilling a glass. Her grandson referred to her as the original W.A.G. They returned to a boarding house in Fulham not far from the Chelsea ground to start their married life. Here my mother remembered one meal prepared by their landlady being placed in front of them. My father was a rather fussy eater and after a moment, “What’s this?” he asked. “Winkles” was the reply. “Winkles? Well. You can winkle them away and bring something else”. I remember my father as mild-mannered and I think it was a bit of a shock to my mother. She was brought up on a farm and would eat virtually anything.

Marriage of John and Edith Sherborne 22nd June 1938. Source: Author’s Collection

By the start of the 1939-40 season war had been declared and a decision was made that as a boost to public morale, football matches would continue to be played. There would be fewer games and some played on a regional basis. A match programme dated 24th December 1939, shows him at inside left in a game against Brighton and Hove Albion. The same programme carries an Air Raid Warning notice with instructions of where to find the nearest cover or Public Shelter. There is also mention of the relaxation of rules regarding qualification of players in regional games. I think this meant that a player could play for another team if his own wasn’t due to play which probably accounts for my father appearing as inside right on the team sheet at Southend United, 30th March 1940. A comment in the same programme says, “Circumstances may compel us to draft several new faces into our team.” It also mentions players who have “…joined the colours.”

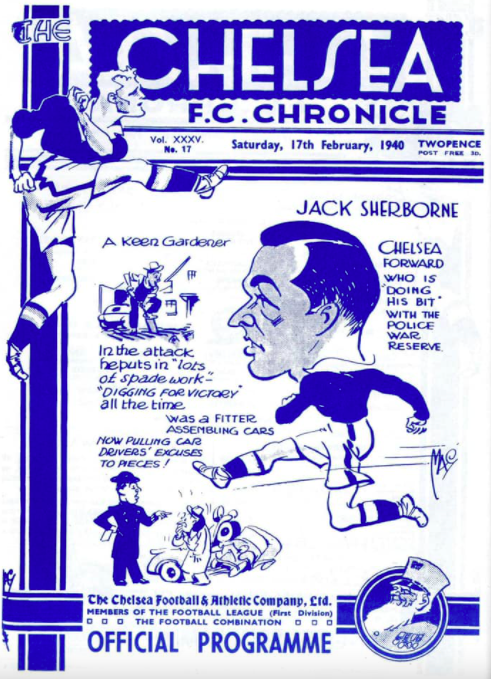

Chelsea FC Chronicle, 17th February 1940. Source: Author’s Collection

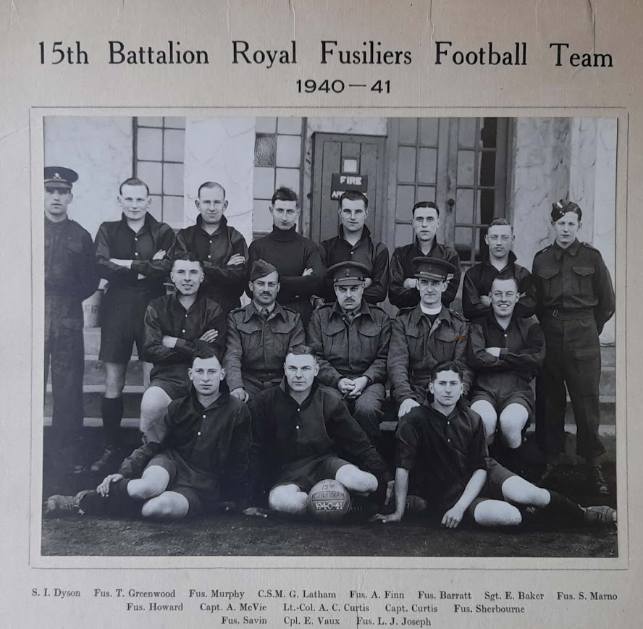

By this time my father was also doing duty as a member of the Metropolitan Police War Reserve and Chelsea were proud to promote the club doing its bit for the war on a programme dated Saturday 17th February 1940. However, by April he, along with some of his Chelsea pals, as he put it, had enlisted. His SSB shows his enlistment on 3rd April 1940 into the 15th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. It didn’t take long for his record stating under former trade: Professional Footballer to be noticed. His Commanding Officer said, “I see you’ve played a bit of football. We could do with you.” Which accounts for his photograph as a member of the 15th Battalion Football Team.

15th Battalion Royal Fusiliers Football Team: 1940-1941. Source: Author’s Collection

After the Dunkirk Evacuation of late May /early June 1940, many of the Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers raised for war service were involved in home defence duties. My father remembered being posted to the area of Kent around Deal. Here he hauled huge rolls of barbed wire which were deployed along the beaches and cliffs and identifying the locations for the positioning of mines. My mother remembered living in Canterbury at this time but when another posting came up in 1941, she decided, as she was now pregnant, to return to her parents’ home in Bolton.

As I mentioned earlier, my father spoke very little of any of his war service and I have very few photos or personal mementos. Wanting to be able to follow his progress through the war years I sent for a copy of his Military Service Records but six months later having received no reply, I decided to investigate various internet sites, used my father’s SSB and found Patrick Delaforce’s book, “The Polar Bears: Monty's Left Flank: from Normandy to the Relief of Holland with the 49th Division” particularly useful in filling in some of the missing pieces.

About 1942/43, the 15th Battalion became absorbed into a re-organised 49th Reconnaissance Regiment formally the West Riding 49th Infantry known as the Polar Bears; a name taken from their 1940/41 duties in Iceland. It was designated an Assault Division as plans were being laid for the future invasion of Europe under the command of Major General Evelyn “Bubbles” Barker whose nickname rose from his vigorous actions and quick thinking. He had a reputation for efficiency and was keen on physical fitness. During 1943, the Regiment trained in Scotland for snow and mountain warfare. They practised beach landings, often under fire from live ammunition and worked alongside tanks and other vehicles. My father did mention being in Scotland on exercises and about an incident whilst using live ammunition when someone in his group accidentally firing a bullet into his ankle.

By early 1944, orders to the Regiment had been changed. Initially the 49th Reconnaissance Regiment were to form one of the assault forces for the D-Day landings, hence the extra Scottish training, but this was to be altered by Montgomery, instead they were to become the follow-up support to the landings. According to Patrick Delaforce, after intensive training for a year there was great disappointment in the Regiment at this news. They were now to provide reconnaissance for the infantry divisions by gathering tactical information, probing ahead and screening the flanks of main advances. Moving now to East Anglia, new intensive training began focussing on field-firing with tanks and artillery, river crossings, road movements and night operations Motor transport drivers practised water-proofing vehicles and driving through deep water. At some point during this time my father became a Driver/Operator in “C” Company the Royal Armoured Corps which absorbed the 49th Recce Regiment. This became a motorised Division under its full name of 49th [West Riding] Reconnaissance Regiment Royal Armoured Corps. I found some information on the Reconnaissance Corp Wikipedia page about the training my father may have experienced. It seems men were selected for training from various infantry divisions but before beginning this training with his unit they had to undergo a five-week course with technical units which would determine his role. These were for driver, wireless operator or mechanic. Most Recce men became proficient at two of these roles. Training also placed emphasis on aggressiveness and initiative to promote a proud offensive spirit. A Recce Regiment contained a Headquarters Squadron and three Recce Squadrons each of which had three scout troops equipped with Bren gun carriers and had light reconnaissance cars, and an assault troop.

My father’s SSB says he was mustered on 8th June 1944, and that his Campaign Service began on 13th June, landing in Normandy as part of Operation Overlord. Over the next few months, the Regiment forced its way across northern France facing fierce resistance from the enemy and with both sides suffering heavy losses as they fought from field to field and village to village. It supported the attack on Caen, taking the village of Rauray and its nearby ridge of high ground. It then held the line between Rauray and Vendes for three weeks carrying out patrols and both receiving and integrating reinforcements. A new offensive was planned which had the Recce Regiment along with the First Canadian Army advancing towards the area between Falaise and Argentan known as the Falaise Gap. This contained large numbers of the retreating enemy. Patrick Delaforce tells how the Recce Regiment moved forward and began reconnoitring in the front of the division. The enemy had withdrawn on the front to the high ground and 49th Recce Regt advanced on the right flank making such rapid progress that in two weeks they had advanced 50 miles and taken 600 prisoners of war.

At the end of August, they had crossed the River Seine and then by 12th September, gone on to capture the important port of Le Havre. Within days of this all the transport of the 49th Division was sent forward to support other units then advancing into Belgium whilst the rest of the Division were allowed a few days recuperation. Soon they were again on the move heading towards an assembly area near Turnout in Belgium and had crossed the Turnout -Antwerp Canal by 24th September. Here they met with such strong and sustained resistance from the retreating enemy that they spent the next few weeks on defensive duties along the Dutch border.

Probable route my father and his Regiment took through Northern France, Belgium and on towards the Netherlands border. Source: Google Maps (Adapted)

It is in this area that my father says his armoured car was sent out on a recce to identify and report back on the enemy positions. The vehicle suffered a direct hit from an enemy shell killing most of its occupants and leaving my father so seriously injured that when rescue arrived, he was thought dead too. However, some sign of life must have been noticed because he was pulled from the wreckage and probably moved to a field hospital which could have been 20 or 30 miles from the front line. My father knew nothing of what was happening to him immediately after the shell hit. He had suffered considerable damage to his skull and the right side of his head, neck, shoulder and shrapnel wounds to his back. He couldn’t recall the place where a metal plate was inserted over the wound in his skull probably somewhere in Belgium. His SSB notes his Overseas Campaign ended on 9th October 1944.

What he did remember was the time he spent at Park Prewett Hospital Basingstoke Hampshire. According to Judy Stokes, a Red Cross nurse, whose contribution comes from the British Red Cross Museum and Archives, eight wards which were located in Rooksdown House situated in the grounds of Park Prewett Hospital were under the leadership of Sir Harold Gillies who was pioneering plastic and jaw surgery. “This was absolutely fascinating work. I had no idea I was taking part in history. It was an absolute privilege to be on his staff.”. Sir Harold Gillies who had trained to be a doctor at St Bartholomew’s Hospital London became interested in plastic surgery following his experiences in World War One. During World War Two, he was responsible for setting up plastic surgery units throughout Britain.

My father remembered being told he was to undergo experimental surgery. Skin to be grafted was grown from the skin of his inner arm and thigh which was then used on his skull wound and to completely rebuild his right ear which had been destroyed. He spent some months there undergoing this treatment but also receiving support for his mental health. The doctors tried to prepare their patients for the possible impacts on their future lives. My mother told her grandchildren that there had been a real concern that my father might not survive or at best be permanently disabled. In fact, he lost the hearing from his right ear and had weakened muscle control to his righthand and arm. My father said they worked miracles.

By June 1945, according to a Pass for Leave issued by Barnsley Hall Emergency Hospital Bromsgrove Worcestershire he was making enough progress to be convalescing and undergoing rehabilitation. He was discharged from the RAC on medical grounds on 26th April, at Barnet Hertfordshire but according to his SSB the effective date was 13th June 1945. His convalescence continued until 1946/47. It was during his time that the doctors advised that on his return home he seek outdoor employment where exercise and fresh air would be of benefit towards regaining his health and fitness. Returning to Bolton my father began work as a postman in November 1948. Initially, this involved delivering mail to outlying moorland farms. It was a job he came to enjoy, fresh air (even the rain and snow) plenty of exercise and the opportunity of meeting people from all walks of life enabling the exchange of views and opinions. This was how he spent the rest of his working life.

As a child of about 5 years old I don’t remember any huge homecoming celebration taking place. There were family gatherings at the homes of my various aunts and uncles which seemed to me to be filled with a sense of relief, pleasure and thankfulness that he had made it home, though I was aware of some concerns over the state of his health, (quiet conversations would abruptly stop if I drew too close) I know my mother carried these concerns for a number of years though my father just got on and slowly rebuilt his life.

Family was important to him and I remember regular family gatherings covering four generations. Although no longer able to play football he retained a lifelong interest, attending local games where his nephew played and supporting Bolton Wanderers. He enjoyed a weekly visit to the greyhound racing track and a flutter on the horses, both these activities he had once enjoyed during his Chelsea days. Always conscious of his health he was careful of his diet. Aware of the benefits of fresh fruit and vegetables he began gardening in order to grow his own. He would never drive again. We travelled by bus, went on moorland rambles at the weekends or caught the train for days out to the seaside, Fleetwood, Morecambe and Southport being favourites. In later life he took up golf to maintain his exercise routine.

He was never bitter about what had happened to him, never complained about the unfairness of it all and never gave any impression of self-pity. He lived a happy life managing to maintain a fairly healthy one [in spite of my mother’s worries] until late into his eighties he was sent for blood tests and x-rays to the local hospital. The results of the chest x-ray completely puzzled the doctors and radiologists who tried to make sense of the scattering of small black spots. It was only when questioned by his young GP that my father explained about his injuries in WW2. He had carried the shrapnel fragments in his back for the whole of his life.

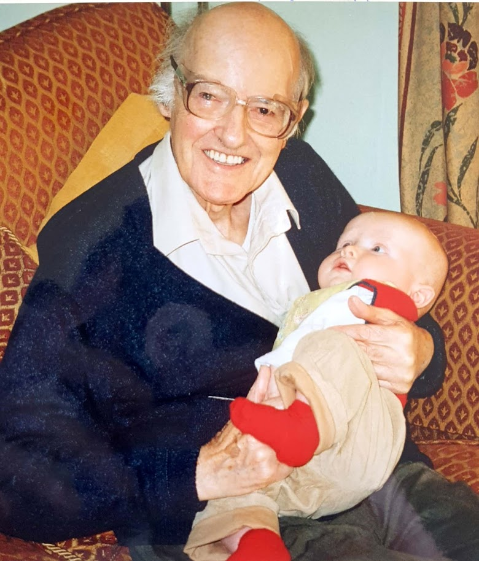

So yes, my father was a hero and a star to me for the way he faced adversity and for the positive way he lived his life. He died 13th March 2007, aged 90.

Jack and his daughter at Knott End (1949). Source: Author’s Collection

Jack with his youngest great grandchild (2005). Source: Author’s Collection

Once when asked some question about his wartime experiences he said, “I lost too many good friends.” I think he would have appreciated this poem by Rob Aitchison taken from the BBC WW2 People’s War.

Longest Day

Do not call me hero,

When you see the medals that I wear,

Medals maketh not the hero,

They just prove that I was there.

Do not call me hero,

Now that I am old and grey,

I left a lad, returned a man,

They stole my youth that day.

Do not call me hero,

When we ran the wall of hail,

The blood, the fears, the cries, the tears

We left them where they fell.

Do not call me hero,

Each night I stop and pray,

For all the friends I knew and lost,

I survived my longest day.

Do not call me hero,

In the years that pass,

For all the real true heroes,

Have crosses, lined up on the grass.

Rob Aitchison

Resources

Chelsea Graves Society link: Chelsea Graves Society on Stamford-Bridge.com

Match Programmes: Chelsea F.C. Chronicle and Southend United F.C. Ltd

Ancestry.com - 1939 Register

UK Postal Service Appointment Book 1737-1969

John Lewis Sherborne’s Soldier Service Book

Patrick Delaforce - The Polar Bears: Monty's Left Flank: from Normandy to the Relief of Holland with the 49th Division With its contributions from all ranks whether through diaries, first – hand accounts, information from official regiment historians, or from photographs and maps this book brings to life and provides fascinating reading about this aspect of WW2. I recommend reading it with an atlas alongside.

Wikipedia - Reconnaissance Corps

BBC World War 2 People’s War:

Pioneering Plastic Surgery contributed by British Red Cross Museum and Archives

Harold Delf Gillies, plastic surgeon [1882-1960] contributed by St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives

The Longest Day by Rob Aitchison

This archive of WW2 memories was compiled by the BBC with contributions from the public or from the archives of a variety of institutions. It can be searched under different categories and contains much interesting and informative material.

Tourist and Motoring Atlas. France 2020, Michelin

Google maps (Adapted)

Biography

Carole Wright was born in Lancashire to Edith (nee Hulme) and John Lewis Sherborne. Educated at Bolton County Grammar School and Coventry College of Education she then worked in Primary Education until her retirement. In 1963, she married Ronald James Wright with whom she had two sons. Her interests have included playing Badminton and Rounders in local leagues, reading, gardening, and researching family and local history. She still lives in Lancashire.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)