Berlin-Baghdad Railway F.C.

13/01/2021 - 1.00

Selim Rumi Civralı

Prisoners being despatched from Junction Station in a captured Turkish Train (Source of image)

At the beginning of the 20th century, Britishness was the dominant cultural myth that shaped Australia's national identity and its relations with the world. According to the Anglo-Australian school, "Britishness was more common in Australia at that time than it was in Britain." In the early days, some colonists like John Dunmore Lang had dreamed “...a British manifest destiny in the Southern Hemisphere”. The leading theorist of Anglo-Saxonism, E.A. Freeman's ideas revived that colonial dream in Australia in the early 20th century. Also, Japan's victory over Russia in 1905 was a threat to the remote dominions of the Empire.

The political atmosphere in Australia was greatly influenced by the intellectual developments in England during the Late Victorian and Edwardian Periods. Thus the building of Australian middle-class masculinity developed largely as the product of imperial admiration in public schools and imitation of the British public school system. The battlefield was likened to the playing field, and strong ties were established between loyalty to the team and loyalty to the King, Country, Britain and the Flag. This affinity between war and sports in Australian public schools was a decisive turning point in shaping the country's national identity.

At that time, the general belief was that a nation should shed enemy blood in war or shed its own blood on the ground in order to prove itself. War was the greatest test of power and courage for a nation. The Australian poet Edward Dyson complained that the Australian lands were not watered with blood in his poem - Men of Australia, in 1898:

“Do ye feel the holy fervour of a new-born exultation?

For the task the Lord has set us is a trust of noblest pride

We are named to march unblooded to the winning of a nation,

And to crown her with a glory that may evermore abide.” (1)

When war was declared on 4 August 1914, it was described in the national press, especially in prestigious newspapers, as an opportunity to write the bravest chapter of a fair young nation's, the "bulldog" generation’s story. Amidst the romantic visions of combat, the Farmer and the Settler proudly pinpointed sport as the maker of its superior recruits (2). The Sydney Mail made similar observations: “The Briton is a born devotee to field sports… The cricketer, the footballer, the harrier, the fox-hunter is not the follower of an idle game, but a happy warrior, cultivating all the factors that make for victory… The cricket-oval, the football field, the tennis court, the harrier trail are in truth training grounds for soldiers.” (3)

Before Gallipoli, there was a perception that the Australian male was unproven on the battlefield. Just before the war started, authors such as Gordon Inglis and C.E.W. Bean popularized the idea that “Australians who beat the world's best athletes in sport would also be successful in the war game”. They thought that Australians had a "sporting spirit", and they could transformed this spirit into heroism in the war. Thus, it would also dispel the opposing claims that the Australians did not actually make progress through Britishness.

The national security, which was Australia's main agenda after 1900, significantly changed the purpose and meaning of sport. As the nation prepared itself for war, physical competition became integral parts of school life and culture. With the declaration of war, the fantasy of playground competition turned into idealism of war for the nation. The links between sport and war in public schools eventually laid the groundwork for the national dogma to be created in the Great War.

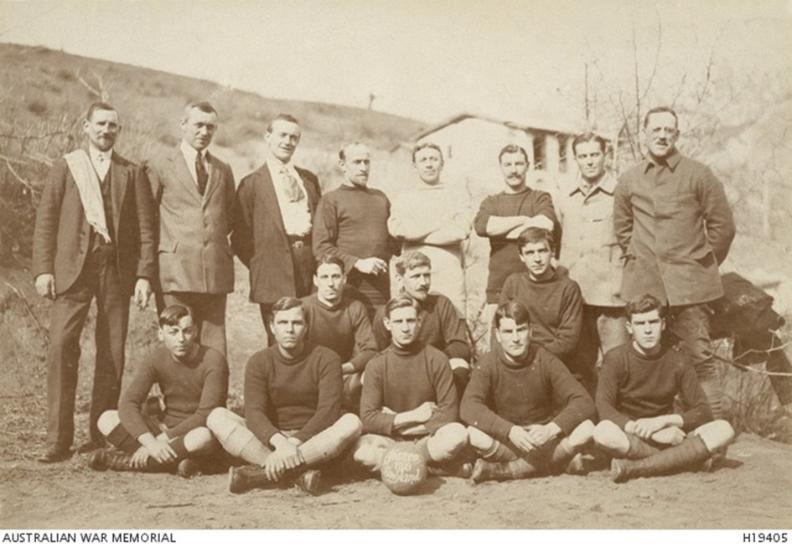

Group photo of members of the English international football team from Turkish POW camps at Belemedick (Source of image)

The unrelenting pressure of the Great War had forced the nation to re-evaluate many aspects of its young self. National and racial identity, relationship with Empire and the wider world, political representation and the role of government, class-consciousness and ethnic division, gender roles and stereotyping, the glory of warfare and the price of military greatness, along with many other issues, came under both affirmation and reconsideration from pre-1914 thinking. The Gallipoli disaster also forced Australians to see that their British dream was an illusion, to acknowledge that Britain was a 'foreign country' and to try to find their own place in the world.

So Gallipoli, rather than the battlefields of the Somme or Flanders, created the image of the Australian at war, the Anzac spirit. The power of the Anzac myth in Australian consciousness made it almost possible for Australians to accept that they had no alternative but to be themselves. The myth therefore emerged out of the disaster that the campaign had become in order to distract from the identity crisis. That was in effect Australia's debut as an independent nation. During the war, 232 Australians were captured by the Turks. Seventy-six of them were captured at Gallipoli (including the entire AE2 submarine crew) and others captured at the Sinai-Palestine front and in Iraq. About 25 per cent of these prisoners died in captivity. These Australians who were captured by the Turks were the first Australian POWs.

Sport’s intermeshing with militarism in the POW camps has become so integral to the Anzac legend and by extension to the emerging national identity that their amalgamation not only survived but thrived throughout the twentieth century. In effect being an independent nation was practiced at Gallipoli and the Turkish POW camps.

The soldiers were kept in the camps until the end of the war. These camps were established in many towns and villages in a wide area stretching from Istanbul in the west to the Taurus Mountains in the east. Officers placed in abandoned houses in and around Afyon were generally better off than the soldiers. Many of them were given a relatively comfortable house arrest. On the other hand, the soldiers were employed on the Berlin - Baghdad Railway project. Both officers and soldiers started to engage in physical activities after a while. In the first letters they sent to their families, they were asking for sports equipment.

As Pat Reid confided in his diary - inactivity could lead to idiocy in a prison camp (4). Captivity caused the prisoners to suffer periodic fits of the blues. The prisoners in Turkey felt the strain.

Sport played a key role in coping with captivity and offered the Australians a means with which to fight boredom, and provided an opportunity for physical and psychological exercise. They saw sport as both a way of overcoming potential depression and a tool for emphasizing their British identity. That’s why the Australians often competed as British within camp sporting competitions. Their triumphs were seen as a victory for the British in the camp and their Australianness was subsumed into Britishness in sporting performance in the camps did not seem to bother Australians, as it indicated their membership of British culture.

Officers, who had more free time than soldiers, lived an active physical and intellectual life. Football, hockey, and cricket became the most popular sports. The Turkish military authorities were reasonably accommodating in allowing rowdy play.

The Australian Red Cross POW Department was the aid agency responsible for the welfare and comfort of all Australian POWs during the war. The prisoners requested sporting gear such as footballs, boxing gloves and cricket apparatus be sent to the camps (5). Equipment was also improvised by the prisoners. Balls were fashioned by wrapping string around pebbles, goals were constructed from Red Cross parcel string, and team outfits were made from scraps of fabric and old uniforms. In some instances, the Turks provided the POWs with sporting gear.

Football, cricket and boxing tournaments were held in the camps. Maurice Delpratt wrote a letter to his sister about his recent participation in a sports carnival organised as part of extended Easter festivities. He competed in 100-metre running, the shot put and long jump and beat French and English athletes in sprint races, came second in the pole vault, and won the egg and spoon race. The sports day was followed by an impromptu concert (6).

George Kerr, also gave information about a football tournament in Belemedik, a labour camp in the Taurus Mountains. Prisoners played for inter-service football teams and later established a boxing tournament, though only on the condition that the two teams did not speak to each other. Army versus Navy was a popular competition (7).

In May 1918, William Randall, a prisoner in the Berlin-Baghdad Railway labour camp, wrote that he did various physical activities, including swimming, in the river outside of working hours. The most interesting of these was a football match between the prisoners and the German employees of the company responsible for overseeing the construction of the Railway. Randall states that they beat the Germans 5-0. After the game, the prisoners were provided with a feed and free drinks (8). In a local newspaper in Avoca, Randall’s home town, it was noted that letters which have reached England described football matches, in which 64 teams (doubtless an exaggeration) had taken part (9).

Another POW, R.F. Lushington explained that at Adapazari, the new Commandant arranged for students from the local agricultural college to play football against the prisoners, who won (10).

Charles Leonard Woolley, a British officer who later became known for his archaeological studies in Ur and Egypt, gave important details about the lives of the officers in the Kastamonu and Gediz camps. For example, in Gediz, matches were held between prisoners who were Oxford and Cambridge graduates. The prisoners at Kastamuni hired a sports field for 15 liras and played football. They manufactured, bought or sent away for the required equipment. Some of it was supplied by the Red Cross (11).

During the winter, cricket and football were giving way to ice hockey and skiing. In 1915 and 1916, winter in Anatolia was harsh; even the lakes were frozen. The prisoners held ice hockey tournaments on the frozen lake. During the heavy snowfalls in 1916, ice hockey matches were held between the Australians, Russians and French (12).

The prisoners were also allowed to celebrate Christmas. Daniel Creedon wrote in his diary that his first Christmas in captivity was unforgettable. Albert Knaggs, one of the crew of the AE2 submarine captured in the Dardanelles in April 1915, noted of Christmas Day 1915 that “...it was made as bright as possible by our Turkish Officers who gave us permission to play football outside in a field. We played a match Navy versus Army in which Army won 4 goals to 1. A concert was held in the evening.” (13)

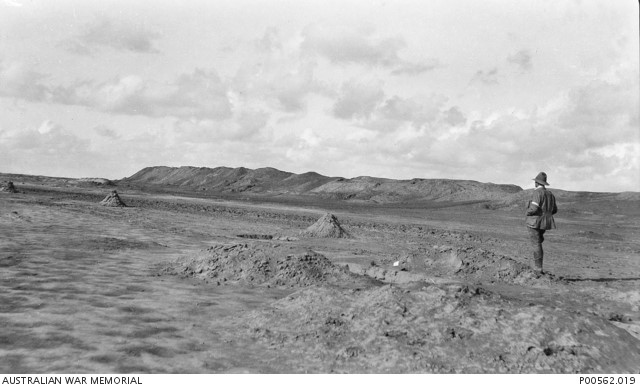

Kut-el-Amara, Mesopotamia, December 12th 1916. A lone soldier looks across the open plains of the Sinn Banks at the beginning of operations against the Turkish Army (Source of image)

The curves of the Australian national identity that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century crystallized in Gallipoli. This identity emerged primarily in an imperial context, and its cultural traffic with Gallipoli has been decisive in its evolution. Ironically, the Anglo-Saxon sports culture, which seems to support the Britishness, revealed tensions and fault lines within the Empire.

Sports in Turkish camps were an expression of British-Australian identity and culture. Heavy defeats and captivity at the front split this identity into two: British and Australian. The Australian identity had become “more Australian and less British”. This chasm was where Australia began to see itself as a nation.

The period 1860-1901 witnessed the emergence of an indirect national identity in the Australian education system and sport. In other words, Australian sport was a sign of national identity, a complex and nuanced combination of imperial unity and localized national feelings. The balance between these elements was disrupted when nationalized symbols, such as athletic soldiers and Anzacs, gradually became more prominent in the narratives during and after the Gallipoli conflict.

Gallipoli was the self- actualization of Australian nationalism that began to manifest its existence literally and culturally since the 1890s. Associating enthusiastic Anzac legend with in the pre-war era ideas was a crucial turning point for Australian nationalism. It showed that the same blood and traditional ties did not make them one people with the British.

As a result, “Britishness” turned into “Anzac” in Gallipoli, and this transformation became a much more important element in identity formation. It is clear the elements within national identity were rearranged through the athletic soldier narratives during the war and then through the captivity narratives. For this reason, Australian identity should be seen as a product of the traumatic experience at Gallipoli.

The sporting community moved to rewrite the history of its place during wartime, highlighting its connection to the glories of Anzac. The Australian historian, Keith Hancock, asserted in 1930 that it was “…not impossible for Australians, nourished by a glorious literature and haunted by old memories, to be in love with two soils”. Hancock underscored this duality of identity by dubbing his compatriots as “…independent Australian Britons” (14).

Thus, Gallipoli is at the core of the sport and war myth that Australia created for the sake of becoming a nation. The beginning of the attack was the end of the imperial obsession of "...the Britain in the Pacific". If "Anzac" is considered the bearer of the Australian spirit, "Gallipoli" is where that spirit was created and given life, which was underlined by the Berlin-Baghdad Railway with double lines. Thus the railway track acts as a metaphor and represents Australianness and Britishness duality of identity.

References

(1) Argus (Melbourne), 1 June, 1898.

(2) Farmer and the Settler, 7 October, 1914, p.2.

(3) Sydney Mail, 3 March 1915, p.37.

(4) Reid, P. Prisoner of War: The Inside Story of the POW from the Ancient World to Colditz and After. London: Hamlyn, 1984, p.157.

(5) C. Cliffe to M. Chomley, November 20, 1917. ARC POW Dept. Case File of William Cliffe, AWM3DRL/428 Box 39.

(6) M. Delpratt to E. White, March 29, 1918. Maurice George Delpratt Correspondence, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

(7) Kerr, G. Lost Anzacs: The Story of Two Brothers. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998, p.139

(8) W. Randall to Mr & Mrs W. Wangemann, May 27, 1918. Papers of Trooper E. Randall 6th ALH and Pte. W. Randall 14Bn., AWM 3DRL/7847.

(9) Avoca Free Press, 15 May 1918. Randall Family Papers, MS B401 BS 1287, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

(10) Lushington, R.F., 1923, A Prisoner with the Turks, Bedford: F.R. Hockliffe, p. 86.

(11)Woolley, L., 1921, From Kastamuni to Kedos. Being a Record of Experiences of Prisoners of War in Turkey, 1916-1918, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 110-111.

(12) Kerr, G. Lost Anzacs: The Story of Two Brothers. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998, p.147.

(13) Diary of A.E. Knaggs, 12. Papers of A.E. Knaggs AE2, AWM PR85/96.

(14) Hancock, W. K., Australia, London: Ernest Benn, 1930. pp 47-58.

Biography

Selim Rumi Civralı, is a Turkish writer and sport historian. He gained his master's degree in Political Science at Yildiz Technical University. In 2019, he completed his doctoral thesis, "Sport as a Struggle Area in International Relations: 1980 Moscow Olympics Boycott". His book, "Athletic Politics: Sport and Ideology", was published in 2020. He undertakes research in political science, philosophy of war and anthropology of sport.

Selim Rumi

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)