An Unprincipled Rogue – A Fan’s Story

08/10/2020 - 5.15

Steve Hunnisett

An Unprincipled Rogue – A Fan’s Story

By

Steve Hunnisett

As well as rightly commemorating the exploits of footballers and the activities of football clubs in wartime, we should never forget that the vast majority of the men who served as civilian soldiers, sailors and airmen during two World Wars, were ordinary working people for whom football would undoubtedly have formed part of their usual peacetime routine. The story of Vic Wilson from Charlton came to light as a result of an innocent query posted on one of the Charlton Athletic fans’ message boards, Charlton Life.

-347x488.jpg)

Vic Wilson (Mark Smith Family Archive)

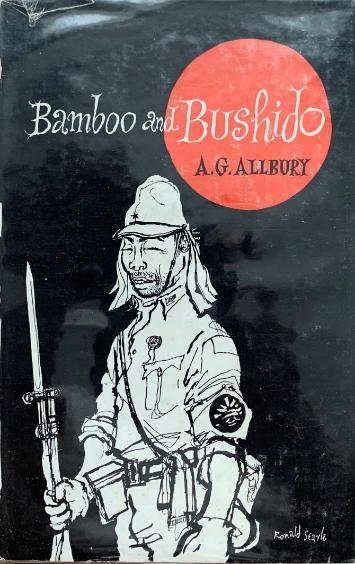

The query emanated from a book that the original poster was reading called “Bamboo and Bushido”, written in 1955 by Alfred Allbury, a former British soldier who tells a remarkable tale of army life, captivity after the fall of Singapore in 1942, brutality at the hands of his Japanese captors and for him at least, a remarkable survival. In the book, Allbury speaks with great fondness for an army pal of his, Vic Wilson from Charlton, whom he describes as “an unprincipled rogue” and the basis of the question posed was whether Vic Wilson was an Addicks’ fan.

“Bamboo and Bushido” book cover, written in 1955 by Alfred Allbury and illustrated Ronald Smith

This was a tall order and a question that I appreciated was unlikely to be answered but being a sucker for punishment, set out to try and answer anyway. There were some clues that perhaps indicated that if he did like football and supported a team, then it might be Charlton Athletic. Firstly, Alfred Allbury and Vic Wilson served with the Royal Artillery, a regiment with strong southeast London connections at Woolwich. Secondly, some quick research into the order of battle at Singapore revealed that a local Territorial battery – 118th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, was indeed present at the fall of Singapore.

We knew that Vic Wilson hadn’t survived captivity and a check of the excellent Commonwealth War Graves Commission website revealed that Vic had indeed served with 118th Field Regiment, so some of the pieces of the puzzle were coming together, although there was a long way to go. Further research showed us that Vic was born in Greenwich in 1918 and had married Violet Elizabeth Brown of Inverine Road, Charlton, during the third quarter of 1939 and had had a baby daughter, Valerie in early 1940. At first, Vic, Violet and baby Valerie had lived at Violet’s parents’ house in Inverine Road but with the onset of the Blitz, Violet and Valerie had moved to the relative safety of Hampshire, whilst Vic’s regiment had been mobilised shortly before the declaration of war.

In normal times, 118th Field Regiment was based at the Territorial Drill Hall in Grove Park but on mobilisation, they had marched the relatively short distance to Woolwich Barracks and for the first few months of the war had been based there. With the invasion threat following the fall of France in June 1940, the regiment had been based firstly on the South Coast and later in East Anglia, on anti-invasion duties. In January 1941, with the immediate threat of invasion beginning to pass, the regiment was posted to the Scottish Borders, at which point the regimental War Diary first mentions the fact that training was being arranged to cover the possibility of the regiment being deployed to a tropical climate. Clearly, although Japan was not officially an enemy at this stage, preparations were beginning to be made.

The regiment sailed from the Clyde on 30 October 1941, for the Far East but took an interestingly roundabout route via Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they were transferred from the eight British troopships into six large American flagged troop carrying vessels, which sailed from Halifax via the Cape on 7 November. Interestingly, the USA was not officially at war and was strictly still a neutral country but a month before their entry into the Second World War, here they were openly assisting their British allies in preparing to fight an enemy who themselves had not officially entered the war!

The convoy reached Bomber on 27 December 1941, where the soldiers were transhipped to British ships in order to complete the final leg of the voyage to Singapore, where they arrived in mid-January 1942, almost in time to go straight into captivity in what was arguably the greatest British military debacle of the war. Despite vastly outnumbering their Japanese enemies, the British forces were poorly commanded and utterly outclassed by their opponents and surrendered on 15 February 1942 in an utterly humiliating fashion.

Alfred Allbury wrote eloquently of the immediate hours prior to the final surrender:

“My co-driver Vic Wilson and I sallied forth on nightly excursions to ammunition dumps scattered around the island-no transport could survive ten minutes on the road by day. Once our 15cwt was loaded, we had to deliver the shells to our guns. This called not so much for knowledge of map reading as for the gift of clairvoyance. Jap planes and the unsuitability of the terrain for effective artillery positions kept our battery commanders roving the island in a desperate search for potential gun-sites. Those found and occupied were speedily made untenable by the sustained accuracy of the Japanese counterfire.

Vic Wilson and I had long been friends. He was an unprincipled rogue with a wry sense of humour, and a healthy hatred of the war that kept him from his young wife and baby back home in Charlton.

On the morning of February 14th the first tentative shells landed among our supply-dumps. They quickly found the exact range and soon a searing bombardment developed that sent us scuttling into our fox-holes. The Japs were ranging on us from heights that overlooked the town. Bukit Timah was theirs after the bloodiest of struggles, the reservoir was stained crimson with the blood of those who had fought so bitterly to hold it, and the little yellow men whom we had ridiculed and despised were in swarm across the island. It was already theirs.

Next morning Vic and I set off on a last mad jaunt taking ammunition to ‘A’ Troop who were dug in behind a Chinese temple to the north of Racecourse Road. Vic drove like a maniac. He had, I found, been sampling a bottle of ‘John Haig’. We thundered along deserted roads, pitted and scarred with bomb craters. Wrecked and burnt-out vehicles lay everywhere, strewn at fantastic angles. The trolley-bus cables hung across the road in desolate festoons which shivered and whined as we raced over them. A few yards from the charred remains of an ambulance were a knot of troops gathered round a cook’s wagon. From them we scrounged a mug of hot tea and found out the guns of ‘A’ Troop were only a few hundred yards distant. We delivered our ammunition and an hour later rejoined Battery HQ close by the Raffles Hotel.

But late that afternoon came the news that we had surrendered. There was to be a cease-fire at four o’clock. We had fought and lost. And the ashes of defeat tasted bitter. At three o’clock all but a few of the guns were silent. Ammunition had been expended. From the hills there still came the occasional bark of a Japanese gun followed by the whine and crash of its shells. But by six o’clock, save for the spluttering of flames and the occasional explosion of ammunition, all was quiet over the island of Singapore. The carnage of the last ten days was quieted now, and in eerie silence our troops sat huddled together in puzzled but fatalistic expectancy.

Vic and I returned to our lorry, ate some tinned bacon and biscuits and stretched ourselves luxuriously for our first uninterrupted sleep for many days. We took off our boots, smoked, talked and listened to the distant caterwauling of the Japanese. “They’ll probably,” said Vic “be crawling round us in the night, cutting off our ears.”

But we stretched out and slept the sleep of the utterly exhausted, while around us into the tropic rose a barbaric and discordant dirge: the victory song of the triumphant Japanese."

-442x655.jpg)

Alfred Allbury (Bamboo and Bushido)

With the fall of Singapore, some 80,000 Allied personnel became Prisoners of War. The Japanese had already signalled their scant regard for prisoners, when the day prior to the surrender, they had captured the Alexandra Hospital. A British lieutenant, clearly displaying a white flag, approached the Japanese in order to act as an envoy and explain the presence of a military hospital but was instead killed by a bayonet. As Japanese forces entered the hospital, they killed soldiers undergoing surgery and bayoneted doctors and nurses with no regard for their non-combatant status. The following day, a further two hundred patients and staff were dealt with in the same bestial manner.

With the exception of some small parties who managed to escape Singapore by small boats, including a group of nineteen from 118th Field Regiment, who safely arrived in India in April 1943, after a fourteen-month odyssey, the vast majority of those who surrendered went into captivity. After initially being held at Changi, many of the men were sent to work as slave labour on the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway and this is where the story of Vic Wilson ends, a victim of Beri-Beri on 27 July 1943 and who thus never returned home to his wife and baby daughter.

The regiment somehow managed to maintain a nominal roll in captivity which records the fate of Vic and his comrades, despite the fact that the writer of the roll remained at Changi with the remainder of the men scattered far and wide. The roll makes for a heart-breaking read and manual count by this writer showed that of the 744 officers and other ranks who went into captivity at Singapore, 188 died whilst POWs, which represented a loss rate of 25.27%. The vast majority of these died from disease but many others died from acts of brutality and entries on the roll such as “Fractured skull caused by rifle butts” are not uncommon.

Despite the sad loss of Vic’s life, this story does have an uplifting ending, as following further research I was able to ascertain that Vic’s daughter Valerie was still with us and living locally. I somewhat tentatively wrote her a letter, explaining who I was and asking whether or not she was aware that her father featured in a book covering the fall of Singapore. A day or so later, I was delighted to receive a phone call and had the first of several pleasant conversations with her. Val didn’t really remember her Daddy, as she was only a baby when he went overseas and neither was she aware of Alfred Allbury’s book. Val’s Mum had of course told her about her father and had frequently told Valerie that she shared many of Vic’s characteristics. She also confirmed that as far as she had been told, that Vic was indeed a football fan and had often attended matches at The Valley before the war. I sent her copies of the pages in which Vic was mentioned and subsequently had another quite lengthy chat. Val offered to send some photos but mentioned that these were with her granddaughter and might take some time to obtain.

There then followed a lengthy gap during which time I heard nothing and I began to wonder whether Val’s family had decided against sending the photos and perhaps wished these to remain privately with the family but just when I thought that the trail had gone cold, I received a phone call out of the blue from Mark Smith, who is married to Val’s granddaughter, who explained that Valerie was in hospital, suffering from the after effects of a nasty fall at home. Mark had found my letter to Val and kindly offered to pick up the baton with regard to the photographs. A few days later, two photographs of Vic arrived via email, including one of Vic and baby Valerie in the back garden of the family home in Inverine Road, Charlton, which shows unmistakeable signs of Blitz damage.

-490x822.jpg)

Vic Wilson and Valerie Wilson (Mark Smith Family Archive)

When the latest addition to the war memorial was unveiled at The Valley just over a year ago, incidentally on the same day as a successful “Football & War” seminar, my friend and fellow guide Clive Harris, a trustee of the excellent Charlton Athletic Museum, stated that although the memorial shows the names of players who gave their all in wartime, the memorial also commemorates everyone connected with the club, whether player, official or supporter who gave their lives during times of conflict.

Vic today rests a very long way from Charlton at the Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery in Myanmar but remains very much in the thoughts of not only his own family but also that of his extended Charlton Athletic family.

As a footnote, Alfred Allbury had a remarkable escape from captivity in 1944. Returned to Singapore from labours on the railway, Allbury was one of 1,317 British, Australian and America prisoners who were loaded onto the Rokyu Maru, a large passenger/cargo vessel for transport to Japan, where they would no doubt be put to work in appalling conditions. The ship was part of a larger convoy, all of which were carrying Allied prisoner. En route, the ship was torpedoed and sunk by the American submarine USS Sealion, which formed part of a larger group of submarines which sank other ships in the convoy. The Allied survivors were left to fend for themselves in the water, whilst the escorts picked up Japanese survivors only. After six days, Allbury and a handful of others were picked up by another American submarine, USS Barb which along with the other submarines in the attacking pack had been ordered to pick up the Allied survivors now known to have been amongst the victims. The Barb rescued thirteen survivors – ten Australian and three British, whilst in total one hundred and forty-nine – ninety Australian and fifty-nine British – were rescued by the American submarines.

Biography

Steve is now a full time Battlefield Guide, military history blogger and researcher, specialising in the Home Front and London at war in particular, who took the plunge into self-employment in 2015. He is a Southeast London boy by birth and splits his football watching time between Charlton Athletic and Dulwich Hamlet FC, being a season ticket holder at both clubs. He has developed a great interest in the history and heritage of both these community-oriented clubs and is the author of ‘For Freedom’, which tells the story of Dulwich Hamlet’s Second World War casualties.

Author - Steve Hunnisett

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)