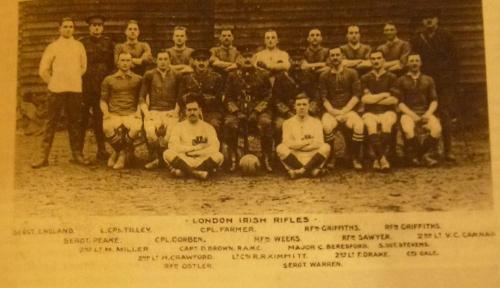

The London Irish Rifles and The Football of Loos

29/03/2019 - 11.33

Tony Robinson

The London Irish Volunteers were founded at the Freemasons’ Tavern, Great Queen Street on 5th December 1859 during concerns over the threats posed by Napoleon III, and which prompted the rise in the Victorian Volunteer Movement. The Marquess of Donegall presided at the original general meeting.

The formal formation of the Regiment took place in February 1860, and at that time was named the 28th Middlesex (London Irish) Rifle Volunteer Corps. The original maximum establishment was a Captain Commandant, 1 Captain, 2 Lieutenants, 2 Ensigns and 200 men of all ranks. Its first uniform was grey with green facings, and a triple sprig of silver shamrock in metal, together with the old-fashioned shako bearing a bunch of cock’s feathers.

The Regiment’s first parade numbered 60, with the Marquess of Donegall as Commandant. Later in 1871, Prince Arthur (Duke of Connaught) became Honorary Colonel of the Regiment, and he would remain so for the next 70 years. Eventually the London Irish were accepted into the army list as a Territorial Army Regiment and first saw action in the Boer War 1900-102, for which they have the battle honour South Africa,

It is worthy of note that when the army went in search of recruits for the Boer War, they found that many of the working-class men were under nourished and very unfit due to the poor social conditions at the time. Going forward, sports including football were actively supported so that the army would be able to recruit relatively fit men and have a base to work from.

At the outbreak of Great War, the London Irish Rifles were mobilised, and more battalions were raised. The London Irish Rifles were part of the 47th London Division. In the Great War the London Irish Rifles suffered a total of 1,016 men killed in action with 2,644 wounded and 303 captured. We were awarded 7 DSOs, 33 MCs, 20 DCMs and 101 MMs to men of the Regiment, and gained 25 battle honours, that were added to that gained by the Regiment during the Boer War.

In this time the size of a battalion could be as many as 1600 men, so football, as well as other team sports were used for fitness as well as to build “esprit de corps”.

There are three footballs which have gained notoriety from the Great War:

- The Christmas Truce Ball of 1914

- The Football of Loos kicked by Rifleman Frank Edwards across at the Battle of Loos in September 1915

- The Surrey Rifles football kicked across during the advance on the Somme in 1916

The Christmas Truce Ball is lost to time and tragically the Surry Rifles Ball was lost in a fire.

As football was actively encouraged for fitness, competition and to build camaraderie it was not uncommon for the troops to have them, but before the Battle of Loos in September 1915, the high command hearing rumours of footballs “featuring” in the forthcoming assault ordered they all be confiscated and destroyed. The memory of the truce that had taken place at Christmas 1914, was still strong and the superior officers wanted a killing force to do just that rather than to have some trivial distraction such as a football.

A young Rifleman called Frank Edwards kept a deflated ball down his uniform front and just before the whistle was blown, he blew it up and as the command came hurled it over the top to the call of “Play on the London Irish”.

The Ball was kicked between Edwards and his team-mates Micky Mileham, Bill Taylor and Jimmy Dalby as they advanced and even when the LIR halted the line of advance, to keep in contact with units to their left and right the ball was kept in play.

The London Irish assaulted the German trenches and cleared through three lines winning the day. They held the line for three days before being relieved.

The whole endeavour was made that much harder as the men were wearing respirator hoods as the British had deployed gas as part of the assault. The gas had stalled as the wind had faded and the soldiers had to fight through it.

Frank Edwards was wounded in the thigh and was aided by Micky Mileham, who was wounded attending to him. They were recovered to the regimental aid station. The ball itself was recovered from the wire.

One of the regimental stretcher bearers that day was Patrick MacGill who after the war became known as the ‘Navvy Poet’ and he wrote the following description:

A boy came along the trench carrying a football under his arm “What are you going to with that?” I asked.

“It some idea, this,” he said with a laugh.

“We’re going to kick it across into the German trench.”

“It is some idea,” I said. “What are our chances of victory in the game?”

“The playing will tell,” he answered.

…It was now a grey day, hazy and moist and the thick clouds of pale-yellow smoke curled high in space and curtained the dawn off from the scene of war. The war was passed along. “London Irish lead on to the assembly trench.” The assembly trench was in front and, there, the scaling ladders were placed against the parapet, ready steps to death, as someone remarked. I had a view of the men swarming up the ladders when I got there, their bayonets held in steady hands and at a little distance off a football swinging by its whang from a bayonet standard. The company were soon out in the open marching forward. The enemy’s guns were busy and the rifle and maxim bullets ripped the sandbags...I went to the foot of a ladder and got hold of a rung. A soldier in front was clambering across. Suddenly, he dropped backwards and bore me to the ground; the bullet caught him in the forehead…I flung my stretcher over the parapet and followed by my comrade stretcher bearer. I clambered up the ladder and went over the top.

The air was vicious, with bullets; a million invisible birds flicked their wings very close to my face…There was no haste in the forward move, every step was taken with regimental precision, and twice on the way across, the Irish boys halted for a moment to correct their alignment. Only at a point on the right there was some confusion, a little irregularity. Were the men wavering? No fear! The boys on the right were dribbling the elusive football towards the German trench.

By the German barbed wire entanglements were the shambles of war…Here I came across dead, dying and sorely wounded;…Here, too, I saw bullet-riddled, against one of the spider webs known as chevaux de fries, a limp lump of pliable leather, the football which the boys had kicked across the field.

The ball was and is kept in the Regimental Museum in the HQ of the London Irish Rifles Flodden Road Camberwell London.

To add to their South Africa battle honour the LIR received many from more from the Great war and from the second world war, in total 67. The LIR still operates today as D Coy London Irish Rifle of The London Regiment based in Camberwell.

There is no longer a requirement to be Irish to join, but you will become Irish by adoption.

A book which is an account of the 1st Battalion the London Irish Rifles in the First World War, has been written by Ed Harris entitled “The Footballer of Loos”.

The Photographic Artist Mike Sheil produced a moving image of the Ball when he returned with it to the Battlefield. His father served in the London Irish in the Second World War and regaled him with stories of it. Below are links to his projects:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WW4pPSDFiok&feature=youtu.be

http://www.westernfrontphotography.com/

Biography

Born and raised in Northern Ireland, Tony Robinson joined the London Irish Rifles in 1992. He served nine years with the regiment before moving on to work with the Regimental Association. He has been referred to as the “Ball Major” as he plays along with the Baldrick association with the Great War and sharing the same name with the actor. All done with the objective of raising funds to support the maintenance of the London Irish Rifles Football of Loos.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)