Floating solar farms can mitigate India's water crisis, says environmental technology expert

Dr Hamid Pouran, Lecturer in Environmental Technology, blogs about floating solar farms in India during India's water shortage.

Hijacked water trucks, fights breaking out in queues for water, and dry taps in schools. These are the latest scenes of India's water shortage.

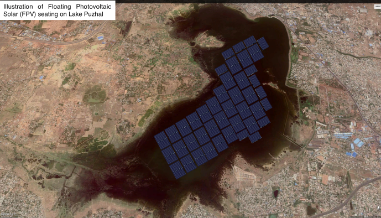

Chennai, a southern city at the Bay of Bengal and the industrial hub for car manufacturers, is at the forefront of this crisis. Over 10 million people in the "Detroit of India" are frustrated as soaring temperatures have turned Lake Puzhal, the city's largest reservoir, into a muddy splat.

Climate change has not been on Chennai's side, and the dry skies have taken their toll. However, it's rapid urbanisation that has made India increasingly vulnerable to this climate emergency.

The government has started investing more in water infrastructures. Approaches like building new dams or inter-basin transfer are under consideration, but we don't know if there is enough water to transfer in the future. Relying solely on such practices will likely lead to a forced awareness that the new environmental conditions require fresh responses and innovative adaptation.

For many years, the government has tried to ease the thirst of a fast-growing Chennai population by desalinating the Indian Ocean waters. But building desalination plants has its side effects. It is a highly expensive method to supply drinking water for a populated city and is not commercially attractive. Moreover, it is energy-intensive, contributes to global warming, and increases the seawater temperature and salinity, which harm the marine ecosystem. Desalination can help when it's considered as one of the available options in conjunction with other methods, for example, overhauling water distribution networks to minimise leaks.

Chennai's water shortage is just one example of a global phenomenon, water scarcity, which has put many cities on alert. Cities like Cape Town and Mexico City are under imminent threat of "Day Zero" when taps run dry across the city. Water shortage is a global problem, but it doesn't mean that the solution is universal too. Every city faces its hurdles to address increasing challenges imposed upon it by climate emergency.

While rapid urbanisation puts pressure on natural resources, new technologies, e.g. smart water meters and leak detection sensors can ease these stresses to some extent. Nonetheless, environmental technologies do not need to be necessarily complicated to be effective.

Floating photovoltaic solar farms, also known as FPVs, are a prime example of such innovations and potentially a crucial approach to mitigate the water crisis in Chennai and many other cities around the world.

The first notable FPV project, with a capacity of over 1 Megawatt (MW), was installed in Japan and connected to the power grid in 2013. Yet, it was the world's largest floating solar farm in China, 70 MW FPV inaugurated in 2018, that attracted the world's attention to this unique technology. The concept behind FPVs is simple; floating parts keep solar panels over the water surface and retained in their place through a series of anchors. The design of FPVs is slightly complex as they need to remain functional for many years and withstand all sorts of environmental stresses, from changes in the water levels to strong winds or possibly earthquakes.

Floating solar farms first emerged in East Asia as an attempt to find an alternative for common solar farms, ground-mounted, where the land prices were too high to be allocated for solar energy. Each megawatt of FPV forms a floating island of roughly about a hectare (10,000 square meters) which is about the same land area required for PV solar farms for a similar output.

Interestingly, this technology presents some unique features that make it a perfect fit for Chennai or any other open water surface. High temperatures diminish the efficiency of PV panels, and in FPVs, the cooling effect of water reduces the panel temperature and increases their generated output.

More importantly, the panels and floating parts cover the water surface and reduce the water evaporation rate, this is apart from reducing direct sunlight, which decreases algae growth and improves the quality of water.

Floating solar farms can be easily and quickly installed on Chennai's largest reservoir, Lake Puzhal. If they sat on the surface of this rain-fed lake, they could adjust themselves with water levels.

When there is torrential rain and even floods, they go up, and when there is drought, they substantially reduce water evaporation from the lake surface. Also, they generate clean and efficient solar energy, which can be used for water desalination plants.

Now the water is almost gone, and Lake Puzhal has turned into a large grey splat. But when the monsoon rains revive it, it doesn't have to become dry again.

Figure 1 is an illustration of how this reservoir would look like when floating solar farms are placed on its surface.

Figure 2. Illustration of how Lake Puzhal would look like when FPVs are seating on the water surface.

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240328-Varsity-Line-Up-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240515-Spencer-Jones-Award-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240516-Andy-Gibson-Resized.jpg)