James Matthews: Minnesota’s Canadian War Hero

08/07/2021 - 2.00

Brian D. Bunk

In the early morning darkness of September 26, 1918, members of the Canadian Army’s 44th Infantry Battalion prepared for combat. A day earlier they had moved into position along the Drocourt-Quêant line, stopping at a small ridge facing a dry section of the Canal du Nord. Even though summer had just been left behind, the nights were cold, and their boots slid and squelched on the wet, slippery ground. The 44th was tasked with an assault on the Canal as part of the Hundred Days campaign, an operation designed to smash the Hindenburg Line and hopefully end the war. Among the men waiting in the chill air was a young soldier from Minnesota named James Matthews.

-603x145.jpg)

Matthews’s entry in his high school yearbook, 1913. Source: The Tiger South High Yearbook, 1913. Hennepin County Yearbook Collection, Hennepin Public Library.

Known as Jimmy to his friends, Matthews left home for Winnipeg in July 1917, so antsy to fight that he couldn’t wait, even though the United States had declared war that April. He initially signed on with the 79th Cameron Highlanders of Canada and sent home a photograph of himself decked out in the unit’s traditional kilt. He signed his Attestation Papers on July 26, 1917, listing his birthplace as Owen Sound, Ontario. In fact, Matthews was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on March 11, 1894 but his family did have roots in Owen Sound.

He attended South High School in Minneapolis where he played basketball and ran track. The Tigers did not have a school sponsored soccer team but at some point Jimmy developed an interest in the game and after graduation lined up for a few local clubs. Eventually, he began playing for the Thistles, one of the most illustrious names in Twin Cities soccer.

.jpg)

Matthews in the uniform of the 79th Cameron Highlanders of Canada. One of his jobs at the paper was drawing the type of linework and framing that appears behind the image. Source: Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 4, 1918.

The earliest matches in the region were played in 1887 and regular competition began a year later. Thistle soon emerged as the area’s dominant squad winning the first three championships. Regular play continued until around the turn of the century when interest in the sport waned and many of the original teams, including Thistle, disbanded. The 1905 and 1906 seasons sparked a revival of the game and, due to the harsh winters, competition was soon divided into spring and fall seasons. A new squad took up the name of Thistle and just like the original side, became one of the region’s most successful clubs.

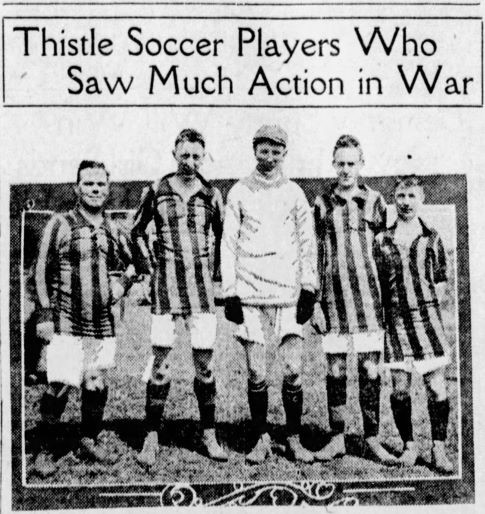

When war broke out in Europe in 1914 some local players moved to enlist, with many choosing to go over the border to join Canadian units. Some of these volunteers never returned. At least four men connected to Thistle perished in the conflict including the team’s former trainer, Thomas Chalmers and goalkeeper Jimmy Robertson. Thistle striker Alex Smith was reported missing and then as dead, but it turned out he had been taken prisoner and eventually returned to Minnesota.

Five Thistle players who served with the Canadian military and survived the war. From left to right: Dave Sharp, Alex Smith, Billy Johnstone, Bob Crichton and Pete McKenzie. Source: Minneapolis Morning Tribune, May 25, 1919.

Jimmy probably wasn’t thinking very much about the risks when he enlisted in the Canadian Army in 1917. As part of the 1st British American Draft, he sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on October 6, 1917 on board the SS Metagama. We don’t know if they were aware of the fact at the time, but other Thistle players, including Alex Smith and Tom Scobbie travelled to England on the same voyage. After disembarking at Liverpool on October 17, Jimmy spent the next few months training and waiting for an opportunity to join the fray. He was offered a job drawing maps but turned it down, explaining to his mother in a letter that “I enlisted to fight, so I’m going to stick with it.” (“Former Tribune Artist in Kilts” – Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 11, 1918). One can only imagine what she thought of that decision. While in England he continued to play soccer and began training for a road race to be held in London. On March 12, 1918 he finally got his chance as he was drafted into the 44th Battalion and was soon sent across the channel to join his unit France.

Jimmy’s first months on the continent were fairly quiet, as the 44th spent much of its time on work details, periodic duty in the trenches or as mobile reserves. They also trained, played baseball and boxed. Members of the battalion competed with other units using the standard soccer code but also took up a game called “massed football.” The rules called for fifty players a side with multiple balls, usually four, in play at the same time. After twenty minutes each team was subbed off and a new set of a hundred men took the field. One point was awarded for a ball kicked over the end line and a goal earned the team four points. On Dominion Day (July 1) 1918, the 44th won the corps massed football championship, out-scoring their rival 75-8.

American Expenditionary Forces Soccer 1918 - 1919 - The beginning of this footage shows what appears to be a game of massed football played by US forces during the war. The rest of the footage shows traditional soccer including bits of a game between US and Canadian troops.

Although the summer of 1918 seemed to have been relatively calm for Jimmy and his mates, they still faced harassment from enemy trench mortars, artillery and aircraft. In August as they moved to positions in preparation for an assault near Amiens, they suffered through a harrowing night raid by German Gotha bombers. Although we don’t know for sure what Jimmy experienced during the attack, he did report a few close calls during the war. Once a piece of shrapnel hit his shoe, a bullet clipped the rim of his helmet and a slug grazed his upper lip. Former Thistle player Tom Scobbie was not so lucky. In many ways, Scobbie’s experiences mirrored Jimmy’s: both had been players for Thistle in Minneapolis, both enlisted at Winnipeg in July 1917, both sailed to England on the Metagama and both were eventually drafted into the 44th. Scobbie was killed in action on September 2, 1918 and it was Jimmy who wrote back home to report that another Thistle man had died.

Jimmy’s fortune would be put to the test again as the 44th prepared for the assault on the Canal du Nord in September 1918. At the appointed hour, the artillery opened up with a barrage designed to wear down the German defenses. The men of the 44th quickly surged forward, some carrying ropes or ladders to scale the twenty foot dikes enclosing the canal. A deadly problem developed as the advancing soldiers quickly overtook the barrage. Soon Canadian shells were raining down on Canadian soldiers as officers and NCOs struggled to recall the troops. All four company commanders were injured in these efforts and several other officers and sergeants were killed.

The speed and relentlessness of the attack surprised the German garrison and it was quickly overrun. Despite facing sheets of machine gun fire, the men of the 44th soon captured their main objective, a sunken road about six hundred yards beyond the canal. By 7:30 am the assault was over and they quickly prepared defensive positions. A total of forty men were killed in the action and over one hundred and fifty were wounded. Jimmy Matthews was not among them.

Two days later Jimmy and his unit prepared for another attack, this time assembling at a site northeast of a village called Bourlon. The shelling began at 6.00 am and due to shortages of ammunition on the German side, the advance was relatively smooth until they arrived near Raillencourt. Here the 44th faced stiff resistance as fierce fighting broke out over control of the village.

The Canadians soon gained the upper hand and the battle turned into a rout as the enemy fled. A few hours later however they returned, launching a series of ferocious counter attacks. The situation of the 44th took a turn for the worse as they ran low on ammunition and a bomb landed a direct hit on a command post, killing three officers. At 3.00 pm that afternoon the Germans once again threw themselves forward and only brutal hand to hand fighting combined with artillery support prevented a total collapse. Hours later, around 10.00 pm, the 44th was ordered to advance to occupy an area along the Cambrai-Douai Road where finally they could rest. The casualty numbers climbed even higher on this second day of operations with a total of seventy-six killed and one hundred and fifty-two wounded.

It is likely that for his actions during this stretch of fighting that Jimmy Matthews was awarded the Military Medal. After the war, his friends and family hounded him for details about what he did to earn such a prestigious honor. Perhaps out of modesty, a continuing sense of esprit de corps or a desire to forget the horrors of close combat, he refused to talk about himself and instead celebrated the actions of his comrades. One soldier Jimmy singled out for praise was Donald B. Martyn.

He was a school teacher before the war and served as a major during the fighting near Cambrai. By the time Jimmy joined the 44th, Martyn had already seen plenty of action. In 1916 he was severely wounded suffering gunshot wounds to his left wrist and thigh, his right foot and leg and both buttocks. He also had a compound fracture of his left foot and a perforated eardrum. The Army sent Martyn home to Canada to recuperate and he only returned to action in the spring of 1918, about a month after Jimmy came into the unit. Jimmy and the other soldiers revered Martyn and felt that they would be okay as long as they had the major with them.

A newspaper article quoted Jimmy explaining Martyn’s actions during the fierce fighting of September 28 “…at Cambrai, with men falling all around him and the rest of us seeking cover where it could be had, the major strolled up the road with the battalion, waving his little stick as if on boulevard parade.” (“Jimmy Matthews; Home from France with British Medal” – Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 6, 1919). For his heroic actions during the conflict, Martyn received the Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross with bar and French Croix de Guerre. He survived the war and continued his military career, eventually obtaining the rank of colonel. Martyn died in 1958.

The combat at the Canal du Nord and Cambrai was some of the fiercest ever experienced by the soldiers of the 44th. The official history of the unit declared “Morally and physically, Canal du Nord and its immediately succeeding operations are the severest ordeal the 44th men have ever undergone. Their achievements in these actions outshine all others in the history of the unit.” (Six Canadian Men, edited by E. S. Russenholt, Winnipeg, 1932, 200). During the course of the fighting the unit recorded over four hundred men killed, wounded or missing and out of the hundreds who began the operation less than a hundred men, two officers and three sergeants remained. Jimmy Matthews was one of them.

After the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, Jimmy was granted a two week leave in Paris. One wonders what the Midwestern boy thought of the war weary French capital. In January 1919, Jimmy was promoted to lance corporal although he reverted to private just a month later at his own request. He sailed for home on May 28, 1919 from Liverpool and disembarked at Quebec on June 6. By the next month he was back in Minneapolis and soon took up his pre-war job as an artist with the Minneapolis Morning Tribune newspaper. Unlike some of his fellow soldiers including Alex Smith, Jimmy did not return to Thistle. Instead, he may have briefly played for another local side known as the Citizen’s Club Albions. He also designed the trophy given to the winner of the local fall season – a plaque depicting a player with a soccer ball at his feet.

.jpg)

Matthews around the time of his death in 1921. Source: Minneapolis Morning Tribune, February 22, 1921.

On the evening of February 19, 1921 Jimmy was out with friends in Minneapolis when he was hit by a street car. The collision mangled his body and dragged him a considerable distance. He was rushed to the hospital where surgeons fought to save his life; his gas damaged lungs did not help. Surrounded by his family, James Matthews died on February 20, 1921. His colleagues at the Minneapolis Morning Tribune published a moving tribute to Jimmy that ended this way:

“Courage flames up on the battlefield to spectacular service. It impels men to great deeds where all the world may see its torch flare forth. But it shines no less splendidly in the common ways of life, to those who have eyes to see; it is a fire no less divine when it lights and warms the lives of those about it in humbler walks, as did James Matthews’ fine steadfastness in peace as in war – steadfastness that arose from the faith and love and right living which lift men upward toward higher things.” (“A Modest Hero” – Minneapolis Morning Tribune, February 22, 1921).

- Christie, Norm. The Canadians at Cambrai. Ottawa, 2004.

- "David Bruce Martyn," Personnel Records of the First World War. Files of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), Library and Archives Canada.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. Ottawa, 1962.

- Minneapolis Morning Tribune

- Six Thousand Canadian Men. Being the History of the 44th Battalion Canadian Infantry, 1914-1919. Edited by E. S. Russenholt. Winnipeg, 1932.

- “James Joseph Matthews” Personnel Records of the First World War. Files of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), Library and Archives Canada.

- The Tiger, South High School Yearbook, 1913, 1914.

- “Thomas Scott Scobbie,” Personnel Records of the First World War. Files of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), Library and Archives Canada.

- War Diary, 44th Infantry Battalion

Brian D. Bunk is a Senior Lecturer in the History Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author of From Football to Soccer: The Early History of the Beautiful Game in the United States published by the University of Illinois Press in 2021.

The text examines various topics in the history of the sport including a chapter on the impact of World War One. He has also contributed essays on football history to the website of the Society for American Soccer History - https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/author/brian-d-bunk/ .

From 2014-18 he produced and hosted the Soccer History USA podcast, available at - SoccerHistoryUSA.org. You can follow Brain on Twitter @SoccerHistoryUS.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/BBR_logo_large.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/Wolves-Story-Thumb.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220505-BAS9-School-Showcase-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/business-solutions/images/banners/business-we-back-you-500x250.jpg)