Football in Occupied Belgium During the Great War

06/03/2020 - 2.29

Filip Walenta

1914 started prosperously for Belgian football. The preceding years saw the sport become more structured with regular regional and national competitions from 1895 and a well-organized new federation that was founded in 1912. The start of the First World War would bring an abrupt and violent end to all good intentions and expectations.

The Invasion and Occupation

From the moment the German troops invaded Belgium on the 4th of August 1914, all sports competitions were cancelled. Thousands of young men were called to arms, among them a lot of sportsmen. Most of them stayed at the Western Front for four long years, some died in the trenches or were taken prisoners of war. Others fled the country and lived in refugee camps in the Netherlands. A few lucky ones escaped the violence of war and stayed in their home town.

However, in November, the southwesterly progression of the German troops came to a standstill near the French border, consequently Belgium was divided into several strategic areas.

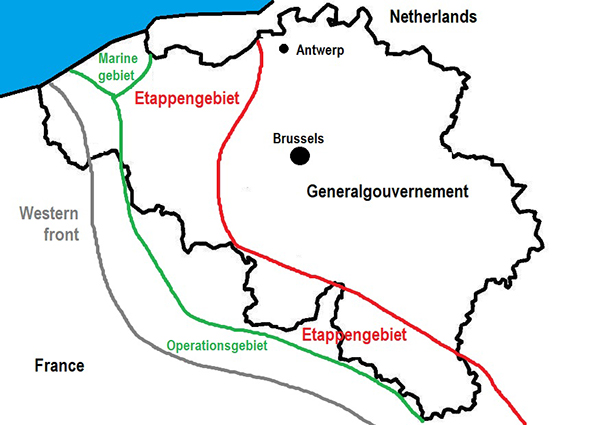

In the fifteen-kilometre wide operations area near the front (Operationsgebiet) and the coastal areas (Marinegebiet), no sport and leisure activities were allowed at all. The rest of occupied Belgium was divided into the Etappengebiet and the Generalgouvernement. The Etappengebiet was a logistical and administrative zone controlled by the 4th German Army for the distribution and supply of fresh troops, weapons, ammunition, material and vehicles, and also a resting place for fresh and returning troops with a lot of (field) hospitals for wounded soldiers. The Generalgouvernement was an area of occupation managed by the German civil authorities.

In order to provide a smooth transition of all the equipment and materials and to avoid revolts, espionage and sabotage, a harsh regime was installed in the whole occupied zone, imposing several restrictions on the mobility and the social life of the local people. Crossing municipal borders, for example, was prohibited as well as all entertainment and festivities on and in public roads and places, as well as all manner of meetings and congresses, especially for political parties and trade unions.

The absence of athletes who were abroad, the decreased mobility in the occupied zone for athletes, referees and clubs, and the crippling effect on sport federations, had an immediate negative impact upon the development and management and of Belgian sporting life at all levels.

Pictured: A map of occupied Belgium with the military zones: Operationsgebiet (frontal zone), Marinegebiet (coastal area occupied by marine troops) Etappengebiet and Generalgouvernement.

Football Players, Clubs, Competitions and the Federation

Of all the sporting athletes, football players were the hardest hit by the war, as most of them were called to arms and stayed on the Western Front. At the end of November 1914, some local informal football games were organized near Brussels and Antwerp, but as the restoration of the country was of bigger importance, the first timid steps to restart regular sports competitions were taken in February-March 1915. It quickly became clear the German restrictions in relation to mobility would make a regular national competition impossible. The newspaper Het Vlaamsche Nieuws reported on January 17, 1915 “… that the expensive and difficult access to other Belgian cities, and the impossibility for the football clubs to demand the same entrance fees as before the war, make it impossible to organize a national or even a partial competition. A regional championship with clubs in Antwerp and its suburbs could generate enough interest, insofar as a solid regulation is provided”.

The football clubs were the first victims of the economic slowdown due to the nearby Western Front and the German occupation, and the nascent professionalism was put in temporary cessation.

In the Spring of 1915, some patriotic chairmen of the Belgian cycling federation - BWB, decided that, out of national pride and symbolic rebellion against the German occupation, all cycling competitions had to be cancelled. Similar actions were also discussed by the football federation. Of course, this decision encountered a lot of resistance and created turmoil. The football clubs feared losing their biggest source of revenue (the entrance fees), the players would lose a part of their monthly income and the fans would not be able to see their favorite team playing. Finally, the federation committee members budged on their proposed action on the condition that part of the entrance fees would be donated to charity.

However, in an important letter from the cycling federation to all its members, organizers and managers of the velodromes, the steering committee declared it was ‘not able to send any representatives or referees to the events’. The football federation faced the same predicament and meant it was not able to manage its member clubs and competitions in an appropriate manner. Consequently, in every city, a local competition was organized with (new) local clubs.

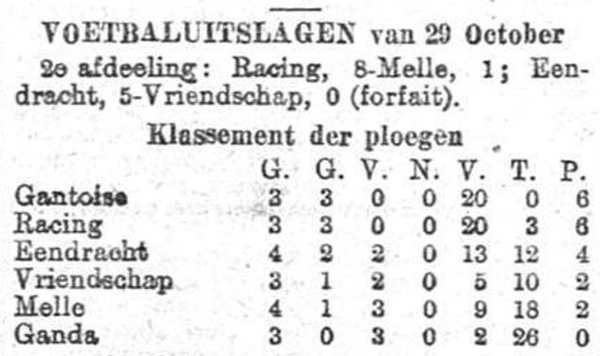

Pictured; Football results and table of the Ghent Second Division competition - October 29, 1916

(Source: Vooruit - November 1, 1916)

Exhibition Matches for Charity

Alongside the local competitions, regular tournaments or exhibition matches were organized with teams containing a mix of the best players of the city. Sometimes they were organized together with other sports to get more spectators and generate more revenue. Mostly, part of the income generated from entrance fees was donated to charity foundations that supported the poor, war orphans or prisoners of war.

The Rise of Football in the Countryside

Strangely, the mobility restrictions had a positive effect upon the democratization process of football as a participation sport. At the end of the nineteenth century, football was only played by students and the bourgeoisie in the cities and their outskirts. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the sport experienced a continuous growth with the founding of the football federation - BVB, but in general it stayed an urban affair.

However, due to cross-municipality border restrictions, local people in the countryside searched for new opportunities to fill their spare time. Consequently, football increased its overall popularity as new football clubs were founded at a fast pace. Stijn Streuvels, a Flemish naturalist author who lived in a small village, wrote in his diary (that was published ten years after his death in 1979): 'The new phenomenon is football, the game that used to be played only by sportsmen and students. Before it was completely unknown in the countryside, but now football is played everywhere. Every village has got its own club and when an appropriate field is found, the game is on'.

Pictured: FC Victoria from Herenthout (near Antwerp) founded in 1916. (Source: De Nieuwe Schakel)

Conclusion

The First World War and the German restrictions were largely responsible for the desportification and deinstitutionalization that occurred at all levels of Belgian football. Most of the players were directly involved in warfare, whilst others were kept prisoners in their own village and could consequently only compete in local competitions. The professional clubs experienced a lot of difficulties in being able to organize decent competitions and faced major problems to survive by lack of resources and decreasing income from sponsoring and entrance fees. The general deinstitutionalization manifested itself at the top level, as the overall governing body, the football federation, was not able to provide any guidance or support during competitions nor to manage the sub-levels of its structure.

Fortunately, the innovative clubs found new ways to keep players in shape and to preserve their football culture until the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

Biography

Filip Walenta is a former competitive triathlete and cyclist, living in Ghent, Belgium. Professionally, he is a meteorologist and currently working as a senior weather forecaster in the Belgian Air Force for the Search and Rescue (SAR) helicopters on the Belgian coast.

As a committee member for about fifteen years and three years as president of his cycling club, Filip founded Karelvanwijnendaele.be, a digital historical research project about the life of Karel Van Wijnendaele, editor-in-chief of the Flemish leading sports magazine Sportwereld at the beginning of the twentieth century and organizer of the Tour of Flanders.

Filip’s research interest lies in the social and cultural history of sports and sports journalism in the nineteenth and early twentieth century in Belgium. As a member of the history organization Ghent-on-Files, connected to the Ghent City Archive, he regularly contributes articles on sports history of the city.

In order to obtain better historical insights and to learn the right skills for historical research, in 2018, he began studying cultural history at the Open University of Heerlen in the Netherlands.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/BBR_logo_large.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/Wolves-Story-Thumb.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220505-BAS9-School-Showcase-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/business-solutions/images/banners/business-we-back-you-500x250.jpg)