Camp Sport - Part 2

03/08/2020 - 1.23

(Introduced by) Anne Buckley

On 27 October 1919, almost a year after the Armistice which brought the First World War to a close, a group of 600 German prisoners of war boarded a train at Skipton railway station to begin their journey home. A number of the men carried with them written accounts, diaries, sketches and poems about their time behind barbed wire in North Yorkshire. Two of the prisoners, Fritz Sachsse and Willy Cossmann, compiled this material into a book entitled Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, which was published in Munich in 1920. A project to translate the book into English has been led by University of Leeds Lecturer Anne Buckley. The translation is due to be published in February 2021 by Pen & Sword and includes an introductory chapter containing research into the camp and the prisoners of war.

This second extract contains a description of sport in the camp and was written in the original German by prisoner Dr Friedrich Eppensteiner. Eppensteiner went on to have a career as a teacher after the war and published a book entitled Der Sport in 1964.

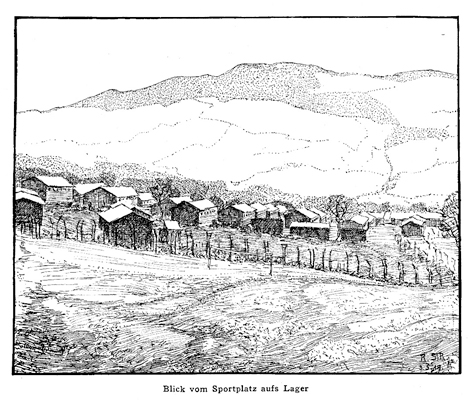

Pictured: View from the sports ground to the camp

Our third main game in the camp, the game of fistball, has something bear-like about it. Just as Goethe’s bear Meister Petz stands up on his hind legs, the fistball player continually returns to take up his position on a particular spot like the chained dancing bear. Initially, observers will notice a certain ungainliness but soon it becomes apparent that the best results are achieved only with the most nimble movements – just as moments of great agility can be witnessed when observing bears. This combination of bear-like power and agility is apparent in the way the ball is handled, one moment hit with resounding force, the next guided lightly forward with a skip and a jump. In fistball there is also an element of the good-naturedness of the bear. The opponents are separated by a rope and only come into contact with each other as a result of ineptitude. Essentially they should have nothing to do with one another, just as polar bears and brown bears are separated by a fence in a zoo. It is only through superior ball handling skills that one can score against the opposing side. It is more a game of skill than a game of combat, akin to billiards and tennis. Therefore it is less crucial to have a series of different opponents to maintain motivation. In contrast to games such as football or basketball, it can be played regularly against the same opposition without a significant loss of fulfilment, as the main satisfaction comes from skilfully striking the ball. In addition, the game only permits five players on each side, so a team can easily be assembled or reassembled if broken up by the extreme irritability typical of prisonörs. The game also requires only a relatively small amount of space, meaning that four games can be played simultaneously. And so it was especially popular in the camp during the hot summer, particularly as little training was required in order to achieve a modest level. For the amateur player it was enough at first if he could thump the ball hard in its English face – what happened to the mistreated ball after that did not really concern him. The spectators would be all the more delighted; the first attempts of a certain team of more senior players were in particular a lasting source of mischievous pleasure for the spectators watching openly or surreptitiously.

Requiring even less prior experience than fistball is basketball, which we should count as the fourth of our main games in the Skipton camp. The technique required is the ability to grasp the ball naturally with both hands then throw it to another player and run – these skills are possessed sufficiently by every healthy person to allow him to pick up the game quickly. While football and Schlagball are played at national level, or could be, basketball and fistball are supplementary games or games played between seasons – fistball more for the warmer months and basketball for the colder months. Fistball is mainly a game for adults, very popular among older gentlemen who have started to accumulate fat around their midriffs; basketball is distinctly a younger person’s game, full of action and bubbling with life. The rule that a player holding the ball with two hands cannot be attacked makes it an excellent game for girls.

As we played it in the camp, basketball was a game of panthers. The agility was cat-like, the leaping, the grabbing, the lithe power, the determination and the resolute tenacity of the best players. Cat fights were common. There was none of the awkward good-naturedness of the fistball bears, none of the humorous scuffles of the Schlagball stars, but also none of the stubborn force of the football buffaloes. No! What we saw there before us were fighting tigers, growing in stature, in the full sinewy strength of their lean bodies. Listen! A threatening growl is emitted from jaws which are attempting to bite. We feel we are only a hair’s breadth away from the beasts drawing blood in earnest. In the days leading up to Whitsun, when the basketball competitions had reached their climax, the behaviour of the spectators and the arrangement of the seating in rows was reminiscent of a Roman amphitheatre. At the front the wide-armed basket chairs represented the boxes of the Caesars and other powerful figures, then came the chairs and the benches of the horsemen, with the shouting plebeians standing behind.

For the sake of consistency I must also include in my animal comparisons the game of tennis, which was taken up by one or two dozen comrades right at the end of the autumn playing season. However, this conflicts somewhat with the overriding significance of the instrument, the racquet, when the game is being practised; the tool is an indicator for the elevation of the human being above the level of animals. Actually, tennis was also considered to be the most refined and aristocratic of all the ball games; certainly for this reason it has more of a tendency than others to incite sports fanaticism and foppishness. Of course, I do not wish to belittle the fine and powerful game. Alongside its particular advantages, every game also has its inherent dangers.

And if we firstly take our eyes off the players and look straight at the ball itself and how it constitutes the moving focal point of performance in the game of tennis – how it flies, springs, bounces, lightening quick, dilated, elastic and yet precise – the image of playing squirrels as a comparison is probably justified. We have discovered two of them playing their delightful games on the trunk of that spruce. They chase after each other up the trunk in short little leaps, we see them appear on the left and on the right alternately, every now and again using adjoining branches to spring from. Similarly the ball sweeps swiftly back and forth over the net. But the rushing of the squirrels up the thin branch is suddenly followed by a magnificent arcing leap to the end of the branch; one of the players has saved himself from a frantic rally by hitting a high volley to the rear of the court in a steep arc with a smooth rotation of his body; the ball slams down firmly and rebounds up again, just as over there the branch bows down under the springing weight of the animal and then springs upwards again. Has the game finished? It almost seems like it has. At any rate one of the animals is sitting calmly at the top of the tree, while the other sits below in the large fork of a branch. But soon one of them makes a sudden movement, to which the other responds with a powerful counter-leap. Well, what did you expect? Likewise, in the game of tennis, after every point there is a pause during which one player prepares himself to serve and the other to return the shot, and only the completed serve initiates once again the swaying, seesawing, springing motion of the bouncing sphere. And when the animals’ game is suddenly interrupted by a mistimed jump or a slip and one of the squirrels falls to the ground from the bough with a heavy thud, it is as much a discordant note as a clumsy shot in the tennis game which sends the ball over the net and beyond the white line into the safety netting – or to use ‘Skipton-speak’ – into the barbed wire. Even the aristocratic nature of the game of tennis is mirrored in the squirrels’ game. The football bull has to wade through the quagmire which often forms in front of the goals; the Schlagball dogs have muck hanging from their bellies (sometimes they also slide along on their backsides across the slippery surface in front of the base line). The basketball tigers and football bears live in their cages, which are not always very clean, but the tennis court on the other hand is clean and smooth or it is empty: the squirrels also only play in the clean and airy areas of woodland trees or in majestic parks. To be truthful, it must however be noted that the over-enthusiasm of some Skipton tennis players, who were sporting novices, did not always conform to this stereotype.

Biography

Anne Buckley is a Lecturer in German and Translation Studies at the University of Leeds. Her research focuses on the POW camp in Skipton, North Yorkshire, where more than 900 Germans were imprisoned during WWI. She has led a team of translators to produce an English version of the 330-page book, Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, which was written by a group of the German prisoners during their incarceration (German Prisoners of the Great War: Captivity in a Yorkshire Camp (Pen & Sword, forthcoming, 2021). She also worked with the Heritage Lottery Fund funded Craven and the First World War project to tell the little-known story of the camp to the local community. In relation to the project, Anne has presented the following academic conference papers: The Legacy of First World War Captivity: A case study of German POWs from a Yorkshire camp, at The International Society for First World War Studies Conference, University of Leeds, 2019; Paper kites and a red balloon: Coping strategies of German POWs awaiting release. 1918-2018: An International Conference, University of Wolverhampton, 2018; and Sherlock Holmes, Saint-Saëns and Schlagball: An analysis of the motivations for the camp activities of officer POWs in WWI using Raikeswood Camp, Skipton as a case study, at the New Research in Military History Conference, University of Cambridge, 2017. The twitter handle for the project is: @skiptonpow

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/BBR_logo_large.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/Wolves-Story-Thumb.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220505-BAS9-School-Showcase-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/business-solutions/images/banners/business-we-back-you-500x250.jpg)