The Beautiful Badge goes to war

25/10/2018 - 3.00

Martyn Routledge and Elspeth Wills

A question of identity

‘It’s about the badge.’ That is how Spurs manager, Mauricio Pochettino summed up the importance of the fierce, little cockerel on his players’ shirts in 2017. Spurs is one of many football badges with a reference to fighting or war ever since the teams from England and Scotland both adopted lions on their jerseys for the world’s first ever international football match in 1872. Many of today’s badges continue the warlike tradition. Colchester United’s and Wimbledon’s badges feature Roman eagles while Doncaster Rovers’ looks back to a Viking past. Recently Stirling Albion featured the Wallace Monument, a 19th-century tower celebrating the exploits of Wars of Independence hero, William Wallace, on its new badge.

The most famous icon has to be Arsenal’s cannon dating back to 1888 when the works team of the Royal Arsenal introduced its first badge. It was based on the coat of arms of Woolwich Borough which featured three cannons with lions at their loading end. Whether facing left or right, against an elaborate shield or simply a red background, the cannon has made an appearance ever since.

Where does the badge come from?

Coats of arms have a pedigree dating back to the 12th century or earlier. When many people could not read nor write and especially in the fray of battle it was useful to have a bold symbol to distinguish friend from foe. Knights attached pennants to their lances and flew flags on top of their tents. Over the centuries landowning families and towns and cities modified such devices as their own heraldic badge. Many football clubs were to adopt elements of these heraldic crests to instil a sense of place among their fans. Football teams found an additional practical value in their badges as marking their opponents on a dark Saturday afternoon before the era of floodlighting.

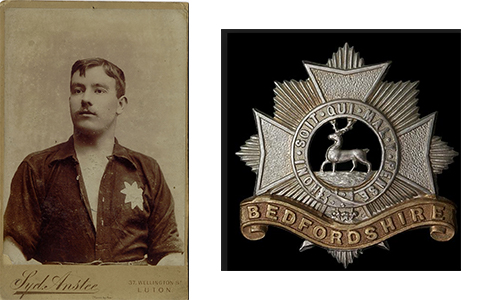

Although many clubs did not adopt a badge until the 1950s some of the earliest were based on simple shapes that could be embroidered on to their jerseys. These also often had military or Empire associations such as Luton Town’s eight-pointed star in the 1890s. The most likely explanation for the star is that the club temporarily played on ground owned by football-lover Captain Carruthers. He was a captain in the Bedfordshire Regiment whose badge was a Maltese cross over an eight-pointed garter star.

The motif of the Maltese cross, or its near-lookalike the cross pattee, was popular in the early years of football. It was also a very popular symbol in the late 19th century, appearing on everything from public school badges to jewellery and the Victoria Cross. It symbolised the knightly virtues that football clubs liked to associate themselves with.

Marching Orders

When the First World War broke out there was much debate as to whether the Football League should continue: after the 1914-15 season the League suspended its programme although individual clubs organised regional competitions. One concern was that football would adversely affect men being called up for the forces. The concern proved to be largely groundless as the game proved a powerful means of turning fans into soldiers. Many teams were so depleted by players signing up to fight that games had to be abandoned.

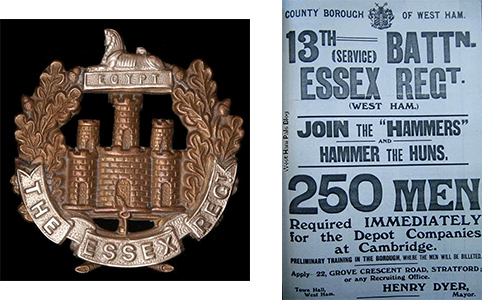

Formed in January 1915, for example, the 13th Battalion of the Essex Regiment was better known as the West Ham Pals because a high proportion of the men were supporters. Its battle cry was ‘Up the Hammers!’ but the War Office turned down the battalion’s application to include West Ham’s two crossed hammers on its cap badge. Using clever wordplay that would not be out of place in a social media campaign today, a recruitment poster had been produced - ‘Join the Hammers, and Hammer the Hun’, in its way as effective as Kitchener’s ‘Your Country Needs You’.

Works’ teams in wartime

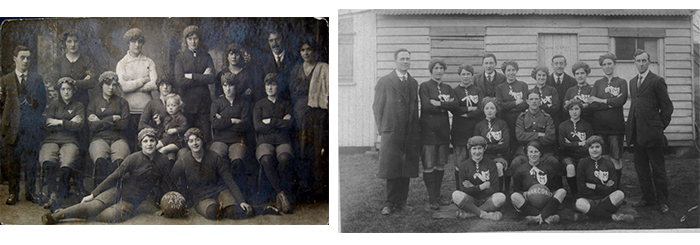

Munitions factories set up their own clubs like Ferranti Amateurs in Edinburgh, the predecessor of Ferranti Thistle and Livingston. Employees of many munitions factories were largely female, bringing ‘young ladies’ into the game decades before the recent popularity of women’s football.

One of the oldest clubs, the Dick Kerr Ladies, was established by women working in the Dick Kerr ammunition factory in Preston to boost morale and raise funds for wounded soldiers being treated in the town. The hugely popular club embraced various badges on its kit, from initials to a Union Jack. Women munitions workers at HM Factory Gretna made up the Mossband Swifts in 1917, choosing to play in shorts rather than skirts. Two of the team wore the triangular ‘On War Service’ badges on their tops. Teams used sashes or other means of identifying themselves from the opposition. The success of women’s football was short lived after the FA banned it in 1921 supposedly on medical and moral grounds. In truth football was seen as a man’s game and women’s football was proving too popular.

Lest we forget

A football badge also provides a reason to commemorate individuals or supporters whose lives were cut short by tragedy, especially during the First World War. Its centenary resulted in several clubs looking into their archives and issuing commemorative badges or more permanent memorials.

One of the first was Heart of Midlothian who as early as 1922 erected a war memorial clock tower featuring its badge at one of Edinburgh’s busiest traffic junctions. In November 1914, 16 players swapped their football boots for Army issue, enlisting to fight in France. They joined McCrae’s Battalion of volunteers, giving it an aura of glamour that no other unit could match. The Battalion also included players and supporters from several teams in east central Scotland. Three Hearts players did not return from the Somme.

As a mark of respect in the centenary season of 2014/15 a commemorative badge was displayed on the team’s top and shorts and the team’s strip carried no sponsorship logos. A decade earlier a commemorative cairn had been raised to all of the men of McCrae’s Battalion at Contalmaison on the Somme, to ensure that the men’s sacrifice would not be forgotten. Fund raising by descendants was matched in their generosity by countless supporters of Hearts and other Scottish teams including Edinburgh rivals’ Hibs. The McCrae’s ‘family’ had reassembled after more than 80 years.

One of the most recent badges to mark the centenary is that of Cowdenbeath. One quarter of its shield of 2015 looks back to the past with the two crosses in one quarter celebrating not only the centenary of the successive occasions in which the team won the Second Division title but also as a tribute to the winning players who then fought in the First World War.

Northampton Town has a war memorial within its grounds whose design includes its badge. It commemorates Walter Tull, the legendary footballer who was the first black officer in the British Army. He died on the Somme in 1918 and his body was never found.

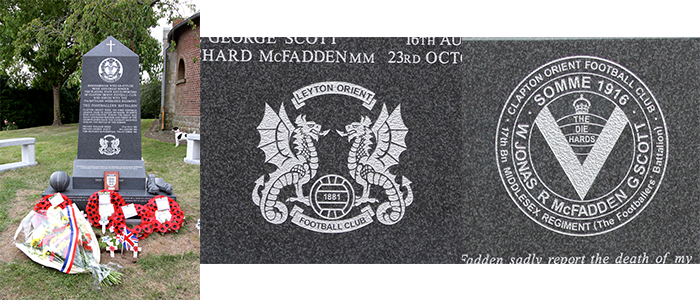

Leyton Orient supporters went a step further and raised funds to build a memorial to team players, staff and fans, in the village of Flers near the Somme. The club, known at the time as Clapton Orient, led the way in answering the call to arms when the ‘football battalion’ – the 17th Middlesex Regiment – was established in 1914 in response to public outcry that professional football stars were continuing to play while other men were being sent to the trenches. Three of its star footballers were killed during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the last words of one footballer being ‘Best regards to the lads at Orient.’

A special badge was created by Steve Jenkins of Leyton Orient Supporters’ Club along with badge collector Len Mitty, to raise money for the memorial. It was inscribed on the memorial along with the club’s current badge. In 2017 merchandise included Somme scarves to pay for the upkeep of the memorial and the badge appears on replica ‘Somme shirts’.

80 years on

The badge is the very essence of a football club. It motivates players and provides something tangible with which fans can identify. Its history, its colours, the town or city it represents, its stadia are all components that help define a football club’s identity. What brings these elements together in an area no bigger than a red card is the badge. Applied, seen, protected and exploited more than ever, from humble beginnings the badge has become the face of the modern club and a valuable and valued asset. It also provides a way of keeping the past alive.

As the approach of the 80th anniversary of the Second World War draws near, people may be inspired to design badges reflecting this era when football stadia up and down the country were regularly bombed. They may choose to commemorate the teams who played badgeless in the prisoner-of-war camps, kit sometimes being provided by the Red Cross. Bolton Wanderers may select their Captain Harry Goslin who at the outbreak of war made an impassioned speech urging spectators to join up and who died in action in 1943. Arsenal may wish to remember its two brave airmen who never got the chance to play for the first team.

Biographical Information

The information in this blog is taken from The Beautiful Badge (published by Pitch Publishing), whose authors, Martyn Routledge and Elspeth Wills, rummaged through the kitbag of history to discover forgotten stories and badges whose meaning has been lost. They have put together the first definitive book on football badges, their history, symbolism and role in the beautiful game.

Since it was published in August 2018, The Beautiful Badge made it to Number 1 on the Amazon best seller list (Sports History), has been featured in numerous design and sports magazines and the authors have appeared on Talk Sport and BBC London Radio.

Martyn Routledge, runs his own design agency (mrcreativestu) working with heritage organisations such as Tower Bridge, as well as sports and leisure brands.

Elspeth Wills is an author and historian.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/BBR_logo_large.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/Wolves-Story-Thumb.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/media-and-communications/images-18-19/220505-BAS9-School-Showcase-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/business-solutions/images/banners/business-we-back-you-500x250.jpg)